The Clamor of the Financiers

January 1932

In December 1931, having been named Minister of Finance, Han Liang was stepping into the shoes of the much higher profile TV Soong, another of his ex-Columbia classmates. Soong had joined Chiang's cabinet in 1928, when Chiang consolidated his hold on power and also married Soong's sister, May-ling.

But being Chiang's brother-in-law didn’t mean that TV Soong and Chiang Kai-shek always saw eye-to-eye. "Brash" is the word that springs to mind to describe Soong, in contrast to Chiang's steely ascetism. With supposedly better English than Chinese and a fondness for press conferences, Soong quickly became the foreign-friendly face of the KMT.

An experienced banker, Soong had proved highly successful in keeping the Nanking government solvent. He had effected a kind of equilibrium whereby the government issued bonds and Shanghai’s bankers soaked them up at steep, agreed-upon discounts. The bonds were secured on the income from various newly created taxes and tariffs. Basically, Soong had worked out a practical solution to the problem of fiscal solvency which Han Liang had written extensively about while at Columbia.

As the Western world succumbed to the Great Depression, China remained largely immune for several more years. Indeed, exports benefited as the country’s silver-based currency depreciated. Soong’s bond market was a system that worked well in these go-go economic times. It was a system clearly superior to Chiang’s earlier approach of relying on Shanghai’s mafia, the Green Gang, to extort "donations” from the business community under threat of arrest, kidnapping or other strong-arm measures. However, by 1931, the cost of waging war against various warlords and the Communists was continuing to rise, while the market for additional bonds was reaching saturation point.

Japan’s September invasion of Manchuria delivered a further blow to the collapsing bond market, but also momentarily checked the squabbling among the KMT factions. On December 15, in a quasi-compromise, Chiang agreed to step down as president of the government, to be succeeded in his executive and honorary roles by Sun Fo and elder statesman Lin Sen, respectively. (Lin Sen was another Fukien native who had attended the Anglo-Chinese College.) But Chiang continued to hold a key position on the KMT's Central Political Council.

Sun struggled to form a viable coalition, and in fact Han Liang was only his fallback choice. Sun’s first choice for finance minister, HH Kung (孔祥熙 Kong Xiangxi), apparently turned him down. Trained at Oberlin and Yale, Kung hailed from an old, prominent and wealthy Shanxi merchant family. Married to the eldest Soong sister, Ai-ling (宋藹齡), Kung was yet another brother-in-law to TV Soong and Chiang Kai-shek. Reluctantly Han Liang accepted Sun’s appeal, knowing he faced an impossible situation.

The new cabinet took office on January 1, 1932. In an article in the English-language People's Tribune, entitled “The Problem Before the Nation”, Sun Fo declared, “I have been left a legacy which is unprecedented. Not only is there not a single cent in the treasury...but my predecessors have mortgaged whatever little available income there is for the next four or five years in advance.” Soong was said to have also removed all of the Finance Ministry’s files and told his staff to view his departure as merely a short holiday, after which he would be back.

In the same magazine, Han Liang said, “My earnest endeavor will be to do my utmost....the nation has been sorely burdened with a load of suffering....To apply the principle of scientific management of tax administration is one of the fundamentals of financial reconstruction in this country.” Another publication of the day described Han Liang as “a well-trained Shanghai banker, facing intelligently the [Ministry’s] dark burdens.” But there was little time for technical knowledge in the world of politics.

On January 4, Han Liang met with Shanghai’s top bankers to introduce a bond stabilization program. He had friends within this group, but knowing that he lacked pull within the inner circle, he had appointed a leader of the majority Chekiang (浙江 Zhejiang) banking group, Lin K’ang-hou (林康猴 Lin Kanghou), as his deputy. Nevertheless, on January 6, when the exchanges opened after a New Year recess, bond prices barely moved. Han Liang was unable to secure more than 5 million yuan in financing from the bankers, compared with Soong’s hundreds of millions.

In the face of Han Liang's failure, Sun Fo took matters into his own hands, choosing a high-stakes route. On January 13, he announced that all bond payments were suspended. There was a hue and cry from the financial community. Han Liang and Lin K’ang-hou had opposed such drastic action and they now resigned. Haggling between the government and the bankers was now personally conducted by Sun Fo. In a compromise deal, Sun proposed that the bond markets re-open and that Han Liang and Lin resume their posts in exchange for the bankers providing the government with 10 million yuan per month for two months. Sun’s measures went into effect, but bond prices remained depressed, and still no money was forthcoming.

On January 22, KP Chen of the Shanghai Commercial Bank, Han Liang's next-door neighbor, wrote in his diary: “Huang Hanliang returned to Shanghai this morning and met with Chang Kia-ngau [and others] at the Central Bank. Needs 10 million yuan for military expenses, 3 million for administrative expenses....Still short 2.5 million yuan. At 5 pm, there was a Central Bank tea meeting. Hanliang went with me, and asked for my help.”

Even Chen’s prestige was insufficient. Chang Kia-ngau (張嘉璈 Zhang Jia’ao, aka 張公權 Zhang Gongquan) was head of China’s largest bank, the privately held Bank of China, and at least in later life would be known to be a dear friend of Han Liang. He and the other bankers would only offer 8 million yuan. Han Liang accepted that amount.

That same day Chiang returned to Nanking from “retirement” in his hometown near Ningpo. Three days later on January 25, Sun Fo, Han Liang and most of the rest of the cabinet resigned, capitulating to realpolitik.

Only days later, simmering tensions with the Japanese boiled over. The industrial Chapei area (閘北區 Zhabei Qu) of Shanghai was fiercely bombarded. The Commercial Press compound where Mo-li’s family had their house was destroyed, along with important silk filatures and many other factories and businesses. Financial markets closed once again.

Ironically, the events of January 1932 closely paralleled a several-month period in late 1927 when Chiang had once before stepped aside due to factional conflict. Back then it had been Sun Fo who had served as finance minister. Facing similar intransigence from the bankers, Sun then had like Han Liang now only been able to raise about 8 million yuan.

Han Liang and Sun Fo surely lacked sufficient influence, but this appeared to be less about them individually, and more about the banking community taking advantage of a moment of KMT vulnerability to register their dissatisfaction about being shut out of having any real political sway, despite having profited handsomely under Soong’s bond regime.

Athough there was no glory to Han Liang’s weeks in office, there was perhaps a measure of honor. On March 16, the famously upstanding KP Chen paid tribute to Han Liang: "after Huang Hanliang's resignation as Minister of Finance, I and [three others] decided to resign from the board of the Central Bank...but Soong asked us to stay on and still sent our letters of appointment by express mail. After receipt of my letter, I replied by express mail, asking again to resign. Soong then came to Shanghai yesterday....” The others weakened, but Chen remained firm, “explaining that I am close friends with Huang. This is a matter of friendship.”

But being Chiang's brother-in-law didn’t mean that TV Soong and Chiang Kai-shek always saw eye-to-eye. "Brash" is the word that springs to mind to describe Soong, in contrast to Chiang's steely ascetism. With supposedly better English than Chinese and a fondness for press conferences, Soong quickly became the foreign-friendly face of the KMT.

An experienced banker, Soong had proved highly successful in keeping the Nanking government solvent. He had effected a kind of equilibrium whereby the government issued bonds and Shanghai’s bankers soaked them up at steep, agreed-upon discounts. The bonds were secured on the income from various newly created taxes and tariffs. Basically, Soong had worked out a practical solution to the problem of fiscal solvency which Han Liang had written extensively about while at Columbia.

As the Western world succumbed to the Great Depression, China remained largely immune for several more years. Indeed, exports benefited as the country’s silver-based currency depreciated. Soong’s bond market was a system that worked well in these go-go economic times. It was a system clearly superior to Chiang’s earlier approach of relying on Shanghai’s mafia, the Green Gang, to extort "donations” from the business community under threat of arrest, kidnapping or other strong-arm measures. However, by 1931, the cost of waging war against various warlords and the Communists was continuing to rise, while the market for additional bonds was reaching saturation point.

Japan’s September invasion of Manchuria delivered a further blow to the collapsing bond market, but also momentarily checked the squabbling among the KMT factions. On December 15, in a quasi-compromise, Chiang agreed to step down as president of the government, to be succeeded in his executive and honorary roles by Sun Fo and elder statesman Lin Sen, respectively. (Lin Sen was another Fukien native who had attended the Anglo-Chinese College.) But Chiang continued to hold a key position on the KMT's Central Political Council.

Sun struggled to form a viable coalition, and in fact Han Liang was only his fallback choice. Sun’s first choice for finance minister, HH Kung (孔祥熙 Kong Xiangxi), apparently turned him down. Trained at Oberlin and Yale, Kung hailed from an old, prominent and wealthy Shanxi merchant family. Married to the eldest Soong sister, Ai-ling (宋藹齡), Kung was yet another brother-in-law to TV Soong and Chiang Kai-shek. Reluctantly Han Liang accepted Sun’s appeal, knowing he faced an impossible situation.

The new cabinet took office on January 1, 1932. In an article in the English-language People's Tribune, entitled “The Problem Before the Nation”, Sun Fo declared, “I have been left a legacy which is unprecedented. Not only is there not a single cent in the treasury...but my predecessors have mortgaged whatever little available income there is for the next four or five years in advance.” Soong was said to have also removed all of the Finance Ministry’s files and told his staff to view his departure as merely a short holiday, after which he would be back.

In the same magazine, Han Liang said, “My earnest endeavor will be to do my utmost....the nation has been sorely burdened with a load of suffering....To apply the principle of scientific management of tax administration is one of the fundamentals of financial reconstruction in this country.” Another publication of the day described Han Liang as “a well-trained Shanghai banker, facing intelligently the [Ministry’s] dark burdens.” But there was little time for technical knowledge in the world of politics.

On January 4, Han Liang met with Shanghai’s top bankers to introduce a bond stabilization program. He had friends within this group, but knowing that he lacked pull within the inner circle, he had appointed a leader of the majority Chekiang (浙江 Zhejiang) banking group, Lin K’ang-hou (林康猴 Lin Kanghou), as his deputy. Nevertheless, on January 6, when the exchanges opened after a New Year recess, bond prices barely moved. Han Liang was unable to secure more than 5 million yuan in financing from the bankers, compared with Soong’s hundreds of millions.

In the face of Han Liang's failure, Sun Fo took matters into his own hands, choosing a high-stakes route. On January 13, he announced that all bond payments were suspended. There was a hue and cry from the financial community. Han Liang and Lin K’ang-hou had opposed such drastic action and they now resigned. Haggling between the government and the bankers was now personally conducted by Sun Fo. In a compromise deal, Sun proposed that the bond markets re-open and that Han Liang and Lin resume their posts in exchange for the bankers providing the government with 10 million yuan per month for two months. Sun’s measures went into effect, but bond prices remained depressed, and still no money was forthcoming.

On January 22, KP Chen of the Shanghai Commercial Bank, Han Liang's next-door neighbor, wrote in his diary: “Huang Hanliang returned to Shanghai this morning and met with Chang Kia-ngau [and others] at the Central Bank. Needs 10 million yuan for military expenses, 3 million for administrative expenses....Still short 2.5 million yuan. At 5 pm, there was a Central Bank tea meeting. Hanliang went with me, and asked for my help.”

Even Chen’s prestige was insufficient. Chang Kia-ngau (張嘉璈 Zhang Jia’ao, aka 張公權 Zhang Gongquan) was head of China’s largest bank, the privately held Bank of China, and at least in later life would be known to be a dear friend of Han Liang. He and the other bankers would only offer 8 million yuan. Han Liang accepted that amount.

That same day Chiang returned to Nanking from “retirement” in his hometown near Ningpo. Three days later on January 25, Sun Fo, Han Liang and most of the rest of the cabinet resigned, capitulating to realpolitik.

Only days later, simmering tensions with the Japanese boiled over. The industrial Chapei area (閘北區 Zhabei Qu) of Shanghai was fiercely bombarded. The Commercial Press compound where Mo-li’s family had their house was destroyed, along with important silk filatures and many other factories and businesses. Financial markets closed once again.

Ironically, the events of January 1932 closely paralleled a several-month period in late 1927 when Chiang had once before stepped aside due to factional conflict. Back then it had been Sun Fo who had served as finance minister. Facing similar intransigence from the bankers, Sun then had like Han Liang now only been able to raise about 8 million yuan.

Han Liang and Sun Fo surely lacked sufficient influence, but this appeared to be less about them individually, and more about the banking community taking advantage of a moment of KMT vulnerability to register their dissatisfaction about being shut out of having any real political sway, despite having profited handsomely under Soong’s bond regime.

Athough there was no glory to Han Liang’s weeks in office, there was perhaps a measure of honor. On March 16, the famously upstanding KP Chen paid tribute to Han Liang: "after Huang Hanliang's resignation as Minister of Finance, I and [three others] decided to resign from the board of the Central Bank...but Soong asked us to stay on and still sent our letters of appointment by express mail. After receipt of my letter, I replied by express mail, asking again to resign. Soong then came to Shanghai yesterday....” The others weakened, but Chen remained firm, “explaining that I am close friends with Huang. This is a matter of friendship.”

Han Liang had been tapped as a thankless walk-on in this ongoing political drama starring the extended Soong clan. Like them inculcated in Christianity, and like all except Chiang formidably US-educated, he was nonetheless not in the running to be one of the country’s new power brokers.

Within a matter of months, Soong was back in office. He offered some concessions to the bankers, but by 1933, his own clashes with Chiang came to a head and he was also pushed out of the Ministry of Finance. Succeeding him now was Sun Fo's first pick, the Soong brother-in-law who Chiang found easier to get along with: HH Kung. Chinese in his modus operandi, restrained where Soong was blunt and amiable where Soong was abrasive, he was at least as wily as his brother-in-law. In 1935, Kung would orchestrate a coup that would bring Chang Kia-ngau and his Bank of China to heel, put all the top banks under government control, and in due course, many industrial companies as well.

A new form of bureaucratic capitalism was emerging. In its subordination of the economic to the political, it resembled the Qing dynasty's efforts at business formation, as well as the current era's state-owned enterprises, suggesting that the free-wheeling free enterprise of the era up to the early 1930s was the anomaly in Chinese history.

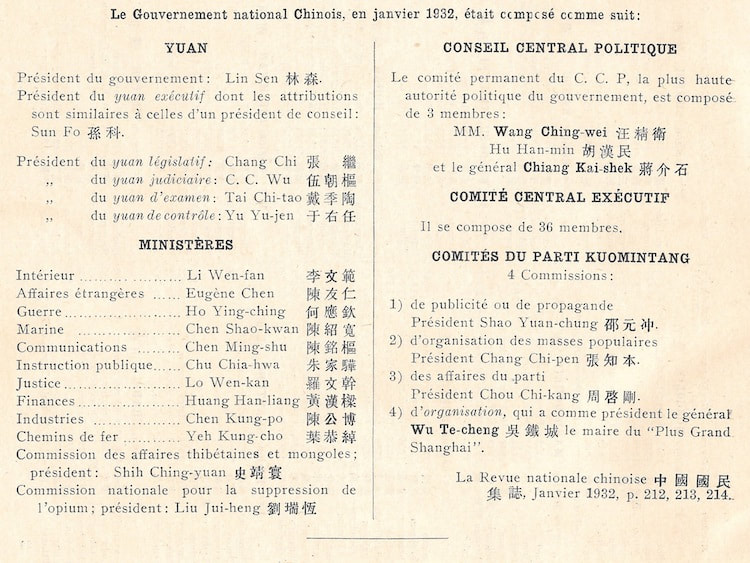

Ironically, in an era of slower communications, a French atlas not published till August 1932 time-capsules the January cabinet. Note that Chiang still held a Central Committee slot along with his arch-rivals Wang Ching-wei and Hu Han-min; and incidentally, titular president Lin Sen was another Fukienese and Anglo-Chinese College alumnus (author's own copy)

|

THE 1935 BANKING COUP & BEYOND

In 1934, with much of the country in a terrible credit squeeze, Chang Kia-ngau began to sell the Bank of China’s holdings of government bonds and use his position as head of the privately held bank that was China’s largest to challenge Kung’s continued policy of coercive bond purchases. He believed the Shanghai banks should be directing their resources to rural and inland areas that desperately needed credit. Kung cleverly turned the tables on Chang and publicly turned the private banks into the bad guys, denying credit to those who needed it most. With the banks on the defensive, Kung forced them to expand their share capital and sell control to the government in return for more government bonds. Simultaneously, Kung maneuvered sympathetic personnel into key management and board positions of the banks and other targeted companies. He also used the financial pressures of the Depression to push companies into bankruptcy, at which point they could be rescued by government takeover. Meanwhile, TV Soong was hardly left out in the cold. Again and again, he and his brothers, TA Soong and TL Soong, topped the list of those named to key positions. The Shanghai business world had always been a tight web of interlocking directorates and influence, but now new types of public-private partnership proliferated and the lines of what was public and what was private became increasingly blurred. |

As the Soong clan and their cronies increased their reach and lined their pockets, Kung’s wife Ai-ling was regularly cited as someone profiting from inside information. Another key figure appointed to multiple positions of influence was Tu Yueh-sheng (杜月笙 Du Yuesheng), the leader of the underworld Green Gang. By now, he too had his own bank, though continuing to also make money from shady activities such as opium and gambling. On the surface, Chiang had cleaned up his fiscal act under Soong and Kung, but in fact, Tu remained very much in the picture as a force of persuasion. Even HH Kung was said to fear him.

Men like Han Liang's friends Chang Kia-ngau, KP Chen and Pei Tsu-yee were frequently named to the boards of companies (as was to a lesser extent Han Liang himself) and new government bodies, but they were in fact relegated to second fiddle with little real sway. Though on the face of it, it may have looked like business interests were completely in bed with government, Chiang’s government was not fundamentally "pro-business". SOURCES This page draws extensively on:

The atlas listing the cabinet is from:

|