Huang Genealogy & Xiamen

Our family is a branch of the Purple Cloud (紫雲 Zi Yun) lineage of Huangs,

and our home village is the hamlet of Bun-tsa/Wenzao (文灶社 Wenzao She), formerly just outside of Amoy.

and our home village is the hamlet of Bun-tsa/Wenzao (文灶社 Wenzao She), formerly just outside of Amoy.

HOMING IN ON "BUN-TSA"

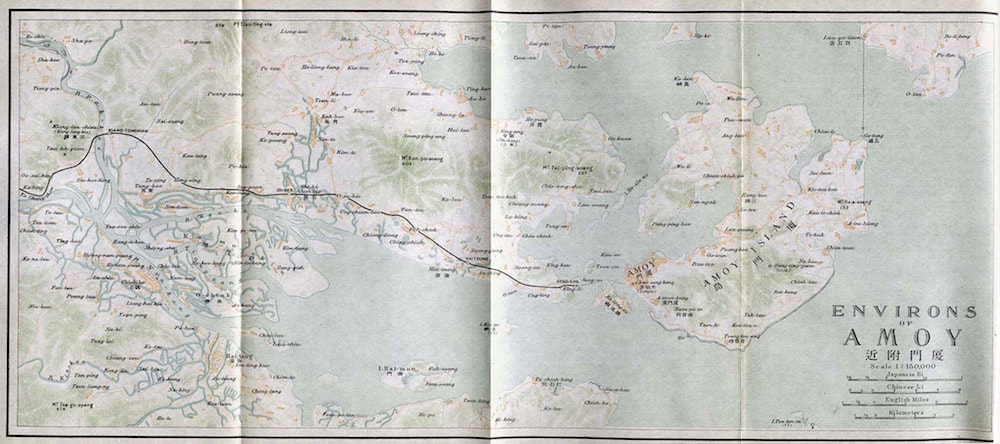

Modern-day Xiamen Island is a circular land mass at the mouth of the river estuary leading to Zhangzhou. It sits halfway between Zhangzhou and Quanzhou, both considerably more populous cities.

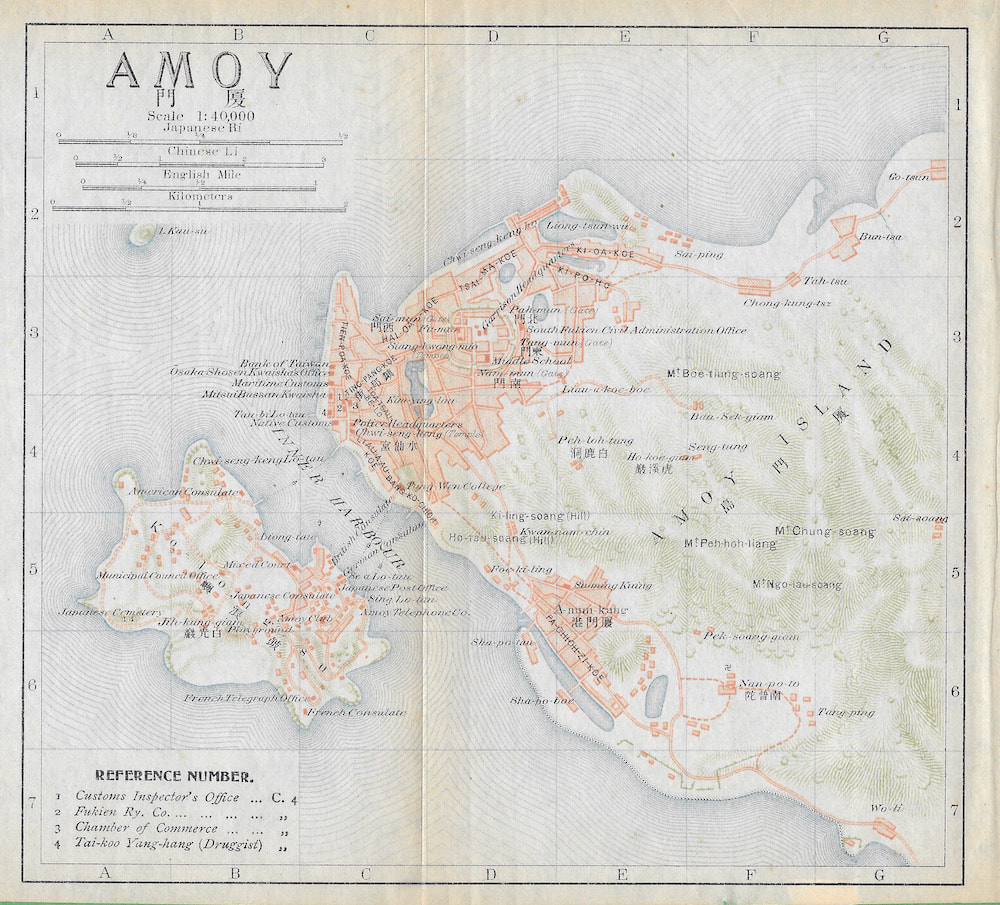

A half century ago, Amoy Island still retained its original reverse “C” shape, with a wide channel cutting into it. The Amoy city center was concentrated on the C's lower lip (shaded orange on the map below). Its waterfront looked out toward tiny Gulangyu/Kulangsu.

The Huang ancestral village was located about a mile and a half east of the Amoy city walls (see circular formation at the center of the orange area below), and was called, in the Hokkien dialect, "Bun-tsa" (文灶社Wenzao She). Bun-tsa is clearly visible in box G2 at the top right corner of this 1915 map:

With the spelling "Wen-tsao", it appears on the right side of this 1945 US government map, as a blue-dotted, triangular swath of flat land:

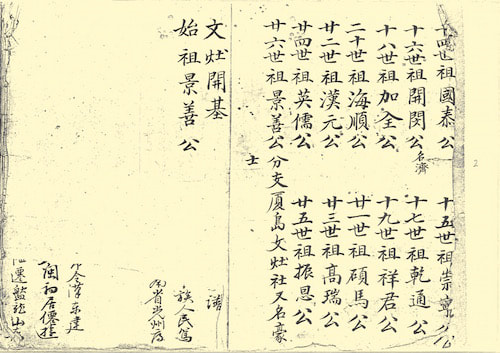

For reasons unknown, Bun-tsa/Wen-tsao/Wenzao was sometimes called "Mazao" (麻灶) and later renamed "Haoshi" (豪士鄉). The village name is cited in a Huang family genealogy that I was loaned by Heling in the 1980s – a modest document, inscribed on brown paper hand sewn into a small booklet of sixty pages. (More about the booklet at the bottom of this page.)

The genealogy includes two sections of lists – one simply of names, the other of names plus birth and death dates and burial locations – plus two narrative sections purporting to trace the family back to 7th century Huang Shougong, who founded the Kaiyuan Temple (開元寺) in Quanzhou, and also to a 9th century migration to Fukien from Henan Province in central China. While virtually every Fukienese must be descended from that individual and that exodus, there is an inherent contradiction in claiming unbroken father-to-son descent from both. There is also the implausibility that flawless records were maintained over forty-plus generations amid the ups and downs of local history.

The genealogy includes two sections of lists – one simply of names, the other of names plus birth and death dates and burial locations – plus two narrative sections purporting to trace the family back to 7th century Huang Shougong, who founded the Kaiyuan Temple (開元寺) in Quanzhou, and also to a 9th century migration to Fukien from Henan Province in central China. While virtually every Fukienese must be descended from that individual and that exodus, there is an inherent contradiction in claiming unbroken father-to-son descent from both. There is also the implausibility that flawless records were maintained over forty-plus generations amid the ups and downs of local history.

Ignore the number penciled in on the right edge of spread. Also note that the yellow tint added to the black and white scans is not original.

To cite just one notable example of upheaval, much property and many lives were lost in the early years of the Qing dynasty when the Manchu court ordered a brutal clearing of China's southeast coast. If our Huang forebears had been in any position to keep written records, they were surely lost then, along with family altars and ancestral tablets. All along the South China coast, from Guangdong to Zhejiang, villagers were forced to abandon their homes and move inland ten or fifteen or more miles. The reason for the evacuation: to undermine an anti-Qing resistance led by Zheng Chenggong, also known as Koxinga.

In the end, the Manchu emperor, Kangxi, who had ordered the evacuations in 1661 and 1662, prevailed against Koxinga and other southern China rebels and went on to rule for sixty-one years, longer than any other Chinese emperor. It took some twenty years before the coastal ban was fully relaxed, but eventually calm returned to Fukien and elsewhere, and towns such as Bun-tsa were settled again. Kangxi was followed by the Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors. Their two reigns extended these times of relative peace and prosperity by another eight decades. It thus makes sense that the first ancestor in the Huang genealogy listed with specific dates is Huang Shihong (黃士宏).

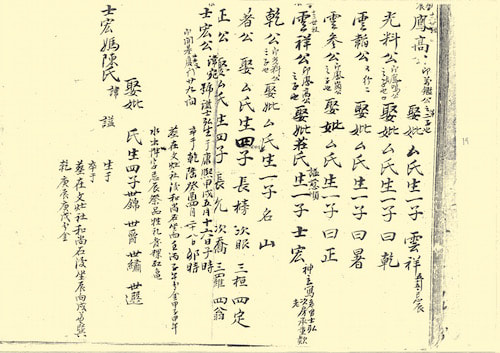

Shihong was born around midnight on the 16th day of the 5th month of the 33rd year of Kangxi's reign (1694) and died at sunrise on the 28th day of the 4th month of the 18th year of Qianlong's reign (1753). Shihong seems to have thrived under these long-ruling Qing emperors: he lived to the age of nearly fifty-nine (by modern reckoning), married a woman from the Chen family, had four sons, and established a residence or other structure with twenty-nine rooms ("即開廈門蘆寓廿九間" ji kai xiamen lu yu nian jiu jian). Our family of Huangs descends from his youngest son Shixuan (黃世選). .

In the end, the Manchu emperor, Kangxi, who had ordered the evacuations in 1661 and 1662, prevailed against Koxinga and other southern China rebels and went on to rule for sixty-one years, longer than any other Chinese emperor. It took some twenty years before the coastal ban was fully relaxed, but eventually calm returned to Fukien and elsewhere, and towns such as Bun-tsa were settled again. Kangxi was followed by the Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors. Their two reigns extended these times of relative peace and prosperity by another eight decades. It thus makes sense that the first ancestor in the Huang genealogy listed with specific dates is Huang Shihong (黃士宏).

Shihong was born around midnight on the 16th day of the 5th month of the 33rd year of Kangxi's reign (1694) and died at sunrise on the 28th day of the 4th month of the 18th year of Qianlong's reign (1753). Shihong seems to have thrived under these long-ruling Qing emperors: he lived to the age of nearly fifty-nine (by modern reckoning), married a woman from the Chen family, had four sons, and established a residence or other structure with twenty-nine rooms ("即開廈門蘆寓廿九間" ji kai xiamen lu yu nian jiu jian). Our family of Huangs descends from his youngest son Shixuan (黃世選). .

Shihong and later his wife were both buried behind Monk's Rock in Wenzao Village. We are given the exact compass directions of their burials, and we learn that offerings of cakes in the shapes of tortoise, symbols of longevity, were made on Shihong's grave. Examples of moulds to make such moulds may be seen on display in a Fuzhou museum:

It must have been Huang Shihong's prosperity that ensured that his details were recorded and compiled into a genealogy by his great-nephew Huang Zhong. Unfortunately it's hard to fathom exactly what it was that Shihong built. Twenty-eight rooms sound grand, but then again those rooms are called "蘆寓", a residence of "reeds" or "rushes", a seemingly flimsy material for building a house, if that is what's meant. Bun-tsa's location along the tidal flats of the Yuan Dang Channel (篔簹港 Yuan/Yun Dang Gang) would have provided ample access to reeds and rushes and presumably the tall variety of bamboo which gave the channel its name. Someone must have profited from harvesting these plant materials, so perhaps they refer to the foundations of a business for Shihong and his family, rather than a house.

Even if later Huangs moved away from the village – to Amoy proper or further afield – it would have been quite normal to choose a burial location close to one's home village. Presumably a geomancer or someone with geomantic knowledge would have been engaged to pick an appropriate site on high ground with the correct seaward orientation – recording these locations seems to be almost the chief purpose of the Huang genealogy, which is otherwise scant on life details. We have the burial locations of twenty-plus male and female ancestors from six generations, starting with Shihong and ending with Han Liang's father's generation. Many are easily identifiable spots dotted across Xiamen Island, such as Rocking Stone or Monk's Rock. Only two forebears are noted as being buried in or near a public cemetery.

Even if later Huangs moved away from the village – to Amoy proper or further afield – it would have been quite normal to choose a burial location close to one's home village. Presumably a geomancer or someone with geomantic knowledge would have been engaged to pick an appropriate site on high ground with the correct seaward orientation – recording these locations seems to be almost the chief purpose of the Huang genealogy, which is otherwise scant on life details. We have the burial locations of twenty-plus male and female ancestors from six generations, starting with Shihong and ending with Han Liang's father's generation. Many are easily identifiable spots dotted across Xiamen Island, such as Rocking Stone or Monk's Rock. Only two forebears are noted as being buried in or near a public cemetery.

However, showing the ancestors respect by tending to their dispersed gravesites must have been a complicated business – no wonder that a written record was desirable! Furthermore, in this part of China, ideal practice was to unbury the dead after a certain number of years and gather the deceased's bones in an urn. The Huang genealogy only mentions two such reburials. It would be interesting to know if those urns were united in one location to simplify the honoring of the dead on Ching Ming, Zhong Yuan and other days designated to honoring the ancestors.

WENZAO STREET: BUILDINGS & BUDDHAS

Today Bun-tsa Village survives as Wenzao Street. Its location is the site of the former village, now part of the city center and no longer on the periphery. The Yundang Channel has been greatly filled in and become Yundang Lake.

On Wenzao Street, tucked among high-rise towers, may be found a Buddhist temple that doubles as a Huang ancestral hall, a sort of community center and focal point for those surnamed Huang.

On Wenzao Street, tucked among high-rise towers, may be found a Buddhist temple that doubles as a Huang ancestral hall, a sort of community center and focal point for those surnamed Huang.

In recent years, community leaders compiled a new Huang genealogy. Like the one for our family, it traces the Huangs of Wenzao back to nearby Tongan on the Fujian mainland (and from there back to Henan and Quanzhou). But it will take more investigation to determine whether the two compilations share any common ancestors.

JIANGXIA HUANGS

In downtown Xiamen may also be found a grander ancestral hall, called Jiang Xia Tang (江夏堂) dedicated to all of the area's Huang lineages, which allegedly trace their origins back to Jiangxia in Hubei Province over 2,500 years ago. It records the names of Huangs who did well in the imperial examinations and houses a Huang Family Association that maintains ties with overseas Huangs, particularly those settled in Southeast Asia. Unfortunately, the Boxer Indemnity Scholarships do not appear to have made it into the canon of reverence.

TONG'AN: CAMPHOR & GARLIC

Our Wenzao hosts took us to still another Huang temple, specific to our lineage and located in the Tong'an area north of Xiamen, in Jin Bing Village (金柄村). It's said to have been established by Huang Lun (黃綸), the fourth of the five sons of the illustrious Huang Shougong. They fanned out from Quanzhou to start new settlements, each with a piece of a brass cymbal. Huang Lun founded his new village where his horse stopped and stamped a hoof on his foot – thus making it a family trait to have a split pinkie toenail.

The current temple building supposedly dates to the Ming dynasty. Recent prosperity has allowed it to be restored after falling into disrepair during the Cultural Revolution.

The current temple building supposedly dates to the Ming dynasty. Recent prosperity has allowed it to be restored after falling into disrepair during the Cultural Revolution.

The village was formerly part of Tongan District (同安區), but in recent years was incorporated into adjacent Xiang An District (翔安區). Residents of the area are mainly farmers supplying much of the world's garlic.

Behind the temple, a park has been created where ceremonies held several times per year draw back Huang descendants.

MORE ABOUT THE HUANG GENEALOGY BOOKLET

|

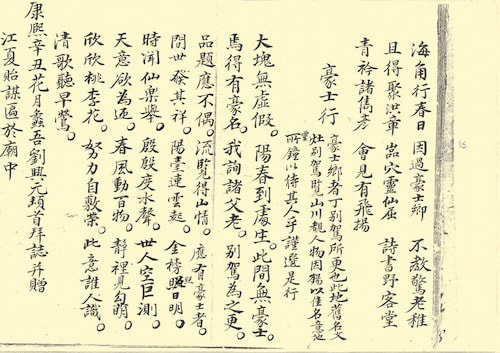

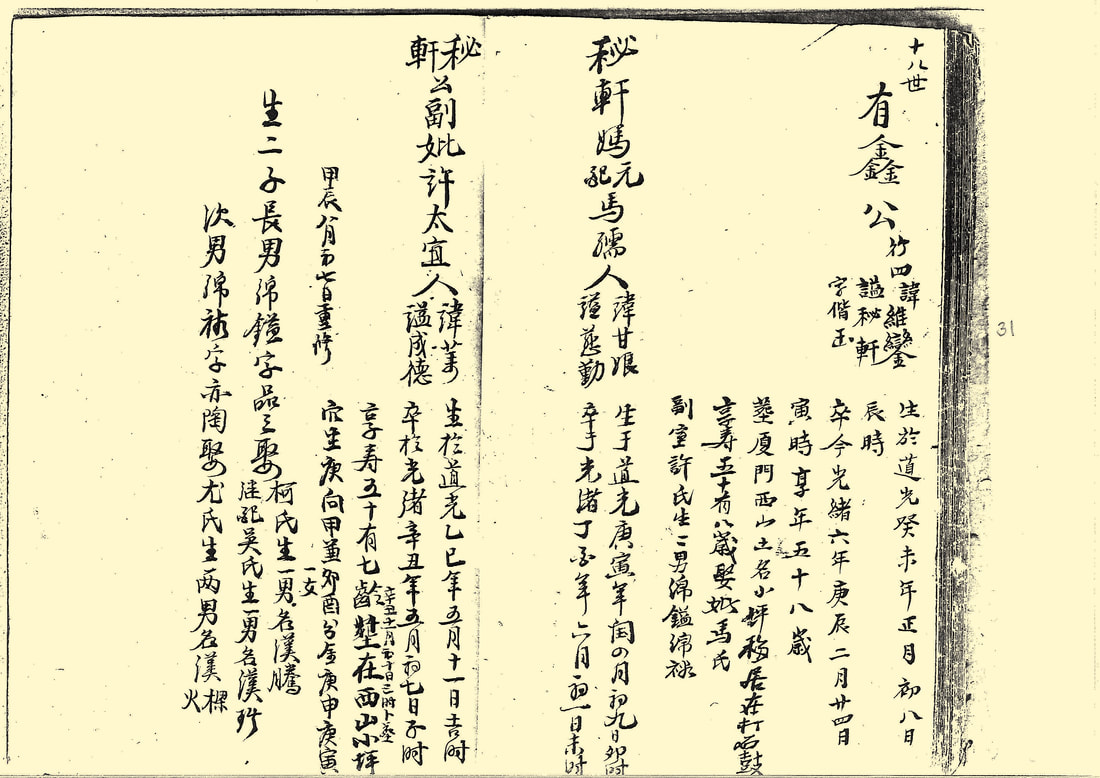

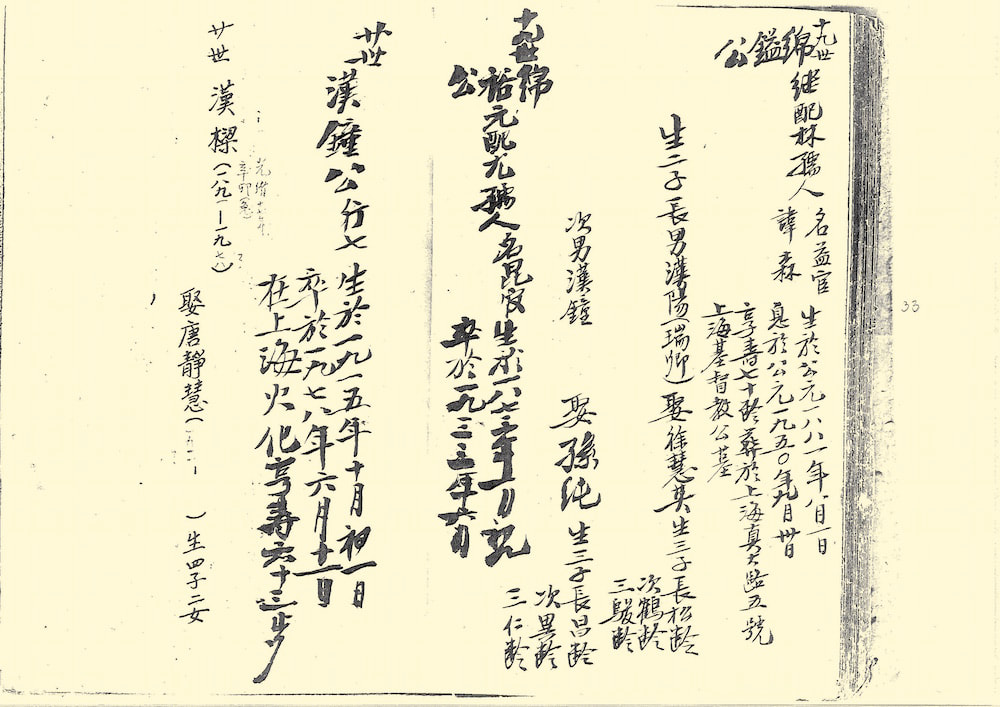

As the document progresses, the handwriting understandably flags somewhat, as if the genealogy were mainly copied out in one go and the copyist’s hand or brush – or both – had begun to fail.

Near the end, the brushwork for entries for Grandmother Yukoon (deceased in 1933) and Huang Chung (deceased in 1978) becomes so rough, one wonders why the calligrapher could not wait for better materials. |

The genealogy is believed to have been put in Heling’s care by Han Liang’s brother Han Ho. Beyond that, Heling knows nothing about the documents origins. A reasonable guess is that Han Ho wrote it out himself. He was the last family member to reside in Amoy, and is known to have been something of a calligrapher and also to have cared in later life about the genealogy’s survival.

But fact that the last entry was written in 1978 or later also makes it impossible for the document to have been written by Han Ho – unless there was a change in calligrapher, though the style of the handwriting suggests not. |