Return to Shanghai

1942-1948

|

At some point in 1942, Han Liang returned to Shanghai with May and Peter, who would have been about eight and seven. They stayed briefly with Han Ho and his family, who were living again in the French Concession in a three-bedroom apartment on Avenue Pétain (now 衡山路 Hengshan Lu). This was near its intersection with Route Cohen (now 高安路 Gao'an Lu), and within short walking distance of the American Community Church where the two couples were photographed nine years earlier.

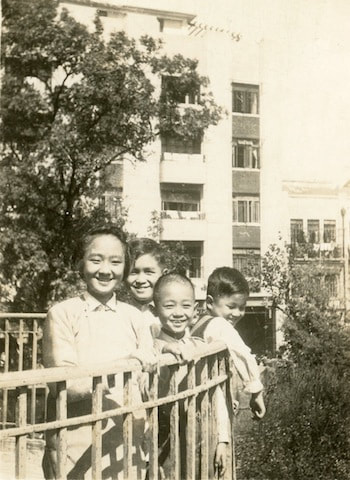

Eventually Zing Wei and the other four children, all under the age of six, joined them. For three years, the family lived in an apartment in Grosvenor House, also in the French Concession. The wife of Han Liang’s cousin Han Yang – Xu Huiying – apparently lived with them, at least briefly, to help out since the family was so large and servants hard to come by. |

|

Their schooling was still erratic at best. It appears that it was well into 1942 or later before any of the children were enrolled in a formal school for the first time, and their experiences would be rather different. May attended the McTyeire School (中西女塾 Zhong Sai Nü Shu), the school of both the Soong and How sisters, that was near the former Yuyuen Road house. But due to illness, May was often kept home from school.

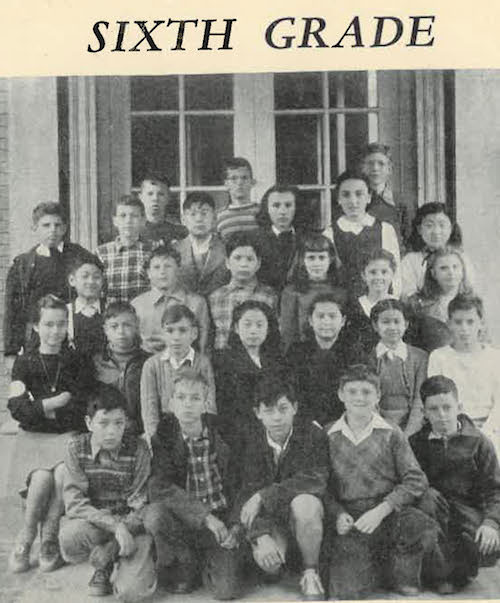

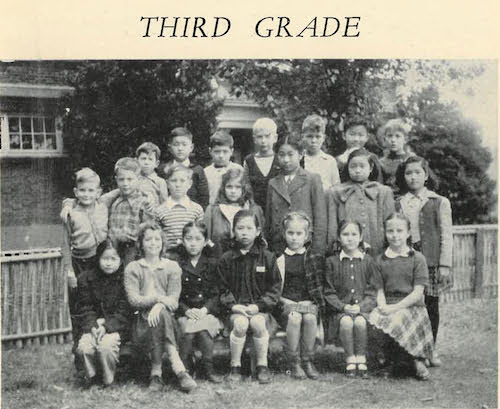

Initially Peter went to Ste. Jeanne d’Arc and Helen to the Sacred Heart Convent School, which was also attended by their cousins Mary and Lulu. Helen apparently had an unhappy experience at the Convent School when the nuns accused her of cheating, and she and Peter soon transferred to the Shanghai American School. Meanwhile, Paul, Stephen and Philip were taught in Mandarin at the prestigious “Awaken the People” Primary School (覺民小學 Jue Min Xiao Xue), which Mary had previously attended and where Philip skipped the first grade. |

|

The family had a car and driver, but sometimes the children might travel to school by rickshaw. The car was believed to be a Packard, big enough for all six kids to squeeze inside, with a running board on the outside.

Most family memories are from the 1055 Yuyuen Road house, yet the Huangs only moved back there in late 1945 after the Japanese surrender. When they moved back to Yuyuen Road, the children were aged five to eleven. May who suffered from asthma and frequently missed school had a room of her own, often kept dark. At least initially, Peter, Paul and Helen shared another bedroom, while Stephen and Philip slept in an enclosed terrace off of their parents’ bedroom. |

|

As the children grew older, the rooming arrangements may have changed, as Helen also recalls sleeping in the enclosed terrace. Paul remembers that May had a fantastic imagination, perhaps from spending so much time at home rather than at school. She would tell wonderful stories and help him with school compositions.

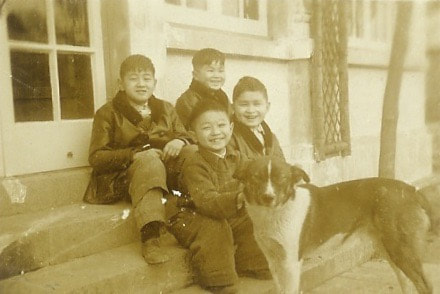

At some point, the family acquired a dog, named "Lassie" after the 1943 movie. Their Lassie had five puppies, enough for each child to name one after him or herself, so long as Stephen and Philip shared the runt with a blind eye and limp. Peter, who received no Chinese instruction at his schools, recalls that a tutor would come to the house to teach him calligraphy. He would practice at a desk in his parents' bedroom until the sweat ran down his arm. On one occasion, Peter went to the kitchen as usual to fetch a bottle of ink and poured the black liquid into the ink stone, only to discover that it was soy sauce. |

A noteworthy feature of Huang family life was that the siblings maintained Cantonese as their home language. The children recall that their parents spoke a mixture of broken Cantonese and Shanghainese, although their mother spoke better Cantonese than their father.

The children also had nicknames, which came from different dialects: May was ”Neui Neui” (lit. "Girl" or "Daughter" in Cantonese, but with a tender overtone more like "Sweetie"), Peter “Lou Lou” ("Piggy“ in Shanghainese), Paul “Yi Yi” (from the second character of his name, which was similar in all the dialects), Helen “Mei Mei” ("Little Sister” in Mandarin), Stephen “Di Di” (Little Brother, more typically Mandarin, but also used in Cantonese with a rising tone for the second "Di"), and Philip “Bi Bi” (Cantonese slang borrowed from English for “Baby").

The children also had nicknames, which came from different dialects: May was ”Neui Neui” (lit. "Girl" or "Daughter" in Cantonese, but with a tender overtone more like "Sweetie"), Peter “Lou Lou” ("Piggy“ in Shanghainese), Paul “Yi Yi” (from the second character of his name, which was similar in all the dialects), Helen “Mei Mei” ("Little Sister” in Mandarin), Stephen “Di Di” (Little Brother, more typically Mandarin, but also used in Cantonese with a rising tone for the second "Di"), and Philip “Bi Bi” (Cantonese slang borrowed from English for “Baby").

Living with them for a time, while attending St. John‘s University, were Michael and Teresa Wang, whom the children called “Goh GOH” and “Jeh JEH” – "Big Brother" and "Big Sister" in Cantonese (哥哥姐姐 gege, jiejie). To avoid confusion, they called Peter and May “GOH Goh” and “JEH Jeh”, with the stress reversed to the first syllable. For some time a student from the Philippines whose name is not remembered also lived with them in the downstairs study, adding bridge to their repertoire of games.

The downstairs study housed classic adventure epics like Water Margin (水滸傳 Shui Hu Zhuan), a complete set of the Commercial Press’ “Wanyou Wenku” (萬有文庫) series, and other well loved volumes, such as The Count of Monte Cristo, translated from the French. There were also occasional shopping trips, when the children had carte blanche to buy all the books they wanted.

The downstairs study housed classic adventure epics like Water Margin (水滸傳 Shui Hu Zhuan), a complete set of the Commercial Press’ “Wanyou Wenku” (萬有文庫) series, and other well loved volumes, such as The Count of Monte Cristo, translated from the French. There were also occasional shopping trips, when the children had carte blanche to buy all the books they wanted.

Helen at the piano, c. 1947 or 1948. This sole interior image, Helen's satin skirt, the cloisonné vases and framed photo of perhaps older sister May at a similar age raise questions about how their daily lives were kitted out and the great distance that Han Liang and Zing Wei had traveled from their own childhoods to this point (R Yhap albums)

The French Club figured highly in their lives, as all of them except Stephen were made to swim competitively under the watchful eye of their father. Although Peter and Helen were the family’s acknowledged athletes, May had a distinctive and elegant style that made her a star at synchronized swimming, and though slight, Stephen was Peter’s agile companion in ball games.

At the Club, they would enjoy Western food such as club sandwiches and french fries – which they recall were always served with mustard, never ketchup. From the Club, they might go on to the Hungjao (紅橋 Hungqiao) country houses of Sun Fo or another family surnamed 黃 (though romanized "Wong"), which owned the ABC textile company and department store, for more swimming in their lake. Years later, Peter Lieu, son of Liu Hongsheng (劉鴻生), Shanghai’s match and cement king (火柴大王 Huochai Dawang, 水泥大王 Shuini Dawang), would lament to Philip that he resented the self-confident gang of children from two families both surnamed Huang.

At the Club, they would enjoy Western food such as club sandwiches and french fries – which they recall were always served with mustard, never ketchup. From the Club, they might go on to the Hungjao (紅橋 Hungqiao) country houses of Sun Fo or another family surnamed 黃 (though romanized "Wong"), which owned the ABC textile company and department store, for more swimming in their lake. Years later, Peter Lieu, son of Liu Hongsheng (劉鴻生), Shanghai’s match and cement king (火柴大王 Huochai Dawang, 水泥大王 Shuini Dawang), would lament to Philip that he resented the self-confident gang of children from two families both surnamed Huang.

Other memories are of childish pitched battles, usually instigated by Peter, with homemade paper darts fired from rubber bands and sofas used as defenses. Glue for home projects was made by boiling down rice and water. There were also mud ball fights around the pond, roller skating races in the driveway, and deliveries of silkworms to play with in the spring time – a common enough plaything, but perhaps somehow connected to the maternal family trade in Wuxi.

That the children would generally prove robust, with Peter, Paul, Helen and Philip growing taller than average and far taller than their parents, is credited to their mother, the former nurse. She made sure that even in wartime they drank plenty of milk and cod liver oil.

We don't hear anything from this time period about visits with Han Ho's family, even though Lulu would have been very close in age to May, and Peter and Helen's Shanghai American School was only a block or so from Han Ho and Peggy's apartment. On the other hand, Han Liang's cousin Han Chung, still living in a lane house nearby, was a regular visitor. The children's impression was that he came for business more than social reasons.

Now in his early 30s, Han Chung had become a banker in his own right, first at the same China Banking Corporation where Han Liang had started his own career a quarter-century earlier (albeit then in Manila). Later Han Chung would move on to the Chiyu Bank (集友銀行Ji You Yin Hang), started in 1947 by Fukienese Tan Kah-kee, who among other things had started Amoy University. Han Liang and Zing Wei also found Han Chung his wife – Sun Chun – when they introduced him to one of the cousins Zing Wei had lived with after her father died.

Now in his early 30s, Han Chung had become a banker in his own right, first at the same China Banking Corporation where Han Liang had started his own career a quarter-century earlier (albeit then in Manila). Later Han Chung would move on to the Chiyu Bank (集友銀行Ji You Yin Hang), started in 1947 by Fukienese Tan Kah-kee, who among other things had started Amoy University. Han Liang and Zing Wei also found Han Chung his wife – Sun Chun – when they introduced him to one of the cousins Zing Wei had lived with after her father died.

The happy-go-lucky memories of childhood stand in sharp contrast to what was going on around them. Within just a few miles of central Shanghai, there were half a dozen Japanese internment camps where close to 7,000 British citizens, including women and children, were held in appalling conditions – although their situation can hardly compare to the misery of hundreds of millions of Chinese in every part of the country. With Japan's entry to the war, China joined the side of the western Allies, which also included Russia. It received support from the US, but arguably very little considering the role it played in keeping some half million Japanese forces occupied. After the Japanese were finally defeated in 1945, the longstanding KMT-Communist rivalry at last broke out into full-fledged civil war, although largely waged in the north of China far from Shanghai.

At home, there were also dark notes. Or at least some of the children were growing old enough to realize that their parents had a rocky relationship. Han Liang treated Zing Wei dismissively – worse than a servant. She was long-suffering. The two argued constantly. Peter and Helen both use the phrase "screamed like a fishwife" to describe their mother's unseemly outbursts. Perhaps this was a phrase they picked up from their father, who by contrast never raised his voice. Han Liang could be very charming to his peers, but he was hard on his wife and demanding of his children. None could question his authority – after all, as he would remind them, he was a PhD!

It was during this time that Zing Wei is believed to have furthered a connection with the Seventh Day Adventists in what appears to have been an on-again, off-again relationship with Christianity. While her pursuit may have been purely on her own initiative, possibly dating back dated to their time in Hong Kong, Zing Wei could also have been influenced by others in their social circle. Many in the KMT leadership, Sun Fo's wife, KP Chen were drawn to the church through its state-of-the-art hospital, the Shanghai Sanitarium. Soong May-ling went as far as employing an Adventist nurse as a traveling companion.

Helen believes that her mother supported the mission by putting the family's Packard at the disposal of church leaders Fordyce Detamore and Henry Meissner. This is plausible as it's known that between April and July of 1948, the church undertook a major evangelical effort in Shanghai, advertising on billboards and street cars. Before long, the church's multilingual services were drawing a thousand people at a time from a wide cross-section of Shanghai society.

Helen believes that her mother supported the mission by putting the family's Packard at the disposal of church leaders Fordyce Detamore and Henry Meissner. This is plausible as it's known that between April and July of 1948, the church undertook a major evangelical effort in Shanghai, advertising on billboards and street cars. Before long, the church's multilingual services were drawing a thousand people at a time from a wide cross-section of Shanghai society.

It's little wonder that Shanghai's populace sought inspiration and comfort at a time when this period of war, first against the Japanese and now between the KMT and the Communists, was stretching into its eleventh year.

THE COLUMBIAN

|

The 1947 yearbook of Shanghai American School (SAS), called “The Columbian”, yields up photos of Peter and Helen in 6th and 3rd grade, respectively.

|

SAS’s main building, water tower and an open area that was formerly the sports field may still be found in Shanghai’s French quarter.

For this project, completed around 1912, campus architect Henry Murphy did not use his signature “big hat” style of other projects in China, where ersatz Chinese roofs sat atop modern concrete shells. Instead, it’s said that Philadelphia’s steepled Independence Hall was his inspiration. However, the woven wooden or bamboo fencing pictured in the yearbook adds a decided local touch.

|

|

SOURCES

Thank you to collector Roy Delbyck, who shared his copy of the yearbook. In less than the time it has taken to research and write the Huang story and launch this website, he has amassed a wide-ranging archive of tens of thousands of books, photos and other publications and ephemera telling the story of Shanghai in the 1920s and ’30s and other aspects of the US encounter with China.

|

For details of the close KMT-Adventist relationship, see:

|