Love-Love: Tennis Anyone?

Tennis, Romance & Six Degrees of Separation in the Republican Era

This page considers a few themes tangential to the site’s main narrative.

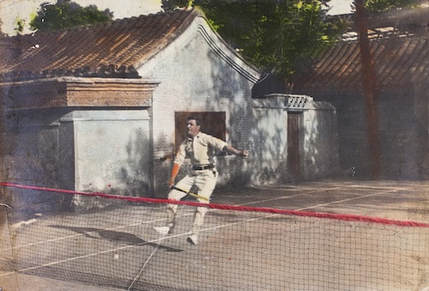

TENNIS

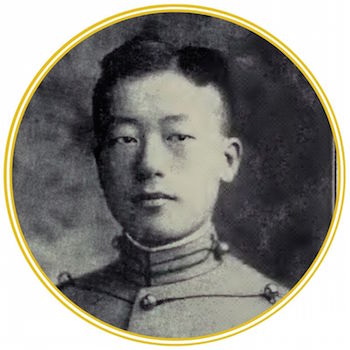

The round photo above depicts the world's first Chinese tennis champion – Wing-Lock Wei of Hong Kong – on the day of his wedding to Australia-born Annie Ng-Quinn in 1916.

In the tennis court photo at the top of this page, Wing-Lock and Annie are seen again (far left) with Annie's sister Rose (fifth from left) and other friends. In 1924, Wei would become Han Liang's distant brother-in-law, when Rose married Bang How and Mo-li How married Han Liang. (Wei was also a classmate at MIT of Han Liang's brother Han Ho – see bio sketch on this MIT web page – though there is no evidence that they knew each other).

Dotted throughout this history are references to… tennis. It was yet another feature of Western life embraced by Han Liang and by his friends, as mentioned in one of Zing Wei’s letters. Notably, the sport also became a well-loved pursuit of most of the Huang children (along with a passion for skiing).

In the tennis court photo at the top of this page, Wing-Lock and Annie are seen again (far left) with Annie's sister Rose (fifth from left) and other friends. In 1924, Wei would become Han Liang's distant brother-in-law, when Rose married Bang How and Mo-li How married Han Liang. (Wei was also a classmate at MIT of Han Liang's brother Han Ho – see bio sketch on this MIT web page – though there is no evidence that they knew each other).

Dotted throughout this history are references to… tennis. It was yet another feature of Western life embraced by Han Liang and by his friends, as mentioned in one of Zing Wei’s letters. Notably, the sport also became a well-loved pursuit of most of the Huang children (along with a passion for skiing).

|

1932 TENNIS VIDEO View priceless footage of warlord Chang Hsueh-liang (張學良 Zhang Xueliang), known as the "Young Marshal", playing doubles with his family on the website of the University of South Carolina "Moving Image Research Collections". (Tennis footage begins at 05:39.) |

Was tennis merely the craze of the day, or did it have other meaning for Han Liang? Did playing demonstrate his success, or in some other way represent the journey he had traveled?

Heling recalls that, in 1951 when he helped Han Ho rent out the Yuyuen Road house, Han Ho pressed on him a set of tennis accessories formerly used to set up games in the Huang garden. The Huang children do not recall tennis being played at home, so perhaps he was mistaken, or maybe they were relics of the 1920s and ’30s. Maybe by the late ’40s, after the Japanese war, Han Liang no longer played, or only played at clubs and friends’ suburban homes.

While in Hong Kong in 1951, what did the Huangs think would become of the Yuyuen Road property, to which it must have been clear they were not returning any time soon? Heling was able to rent the house to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and to this day many of the families living in it are still Academy staff. Heling says that the garden was soon built over, definitively ruling out further tennis matches.

Heling recalls that, in 1951 when he helped Han Ho rent out the Yuyuen Road house, Han Ho pressed on him a set of tennis accessories formerly used to set up games in the Huang garden. The Huang children do not recall tennis being played at home, so perhaps he was mistaken, or maybe they were relics of the 1920s and ’30s. Maybe by the late ’40s, after the Japanese war, Han Liang no longer played, or only played at clubs and friends’ suburban homes.

While in Hong Kong in 1951, what did the Huangs think would become of the Yuyuen Road property, to which it must have been clear they were not returning any time soon? Heling was able to rent the house to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and to this day many of the families living in it are still Academy staff. Heling says that the garden was soon built over, definitively ruling out further tennis matches.

SOCIAL NETS

The more one learns about China’s Republican period, the more it seems that the influential elite was confined to a mere handful of families, many educated in the West or by Western missionaries. Through marriage, they often became intricately intertwined, as evidenced by the discovery that Han Liang could claim more than mere sporting kinship with Wing-lock Wei.

Of course, there are the famous Soong siblings. A notch or two down in fame are seven families featured in York Lo’s 東成西就 (East & West: Chinese Christian Families and Their Roles in Two Centuries of East-West Relations) – among them, the Bao/Bau clan of Mo-li’s mother and uncles who helped co-found the Commercial Press. Lo's book details the seven families’ interconnections and descendants, with passing mention of Han Liang and his children.

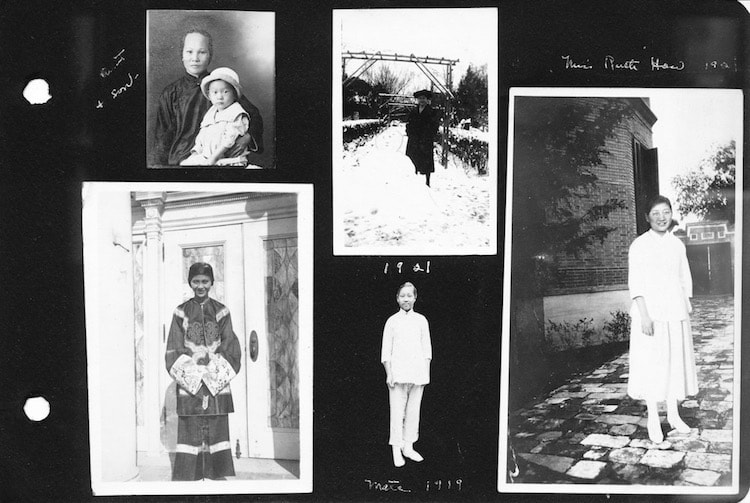

Also connected to those families, though unrelated to the Huangs until a wedding in the 1960s, was the family of my maternal grandmother, Lily Ho Quon. Born in Hawaii, Lily grew up in Nanking. She was, I believe, acquainted with the How sisters through their aunt (their mother's sister; maiden name "Bau"), whom Lily called "Aunt Kuo". Aunt Kuo had married into the Kuo family and had a niece, Maida Kuo, who would become Lily's lifelong friend. Lily’s photo albums include many photos of Maida, some of Aunt Kuo and also, serendipitously, some of the How sisters. In recent years, as I figured out the identity of Mo-li, it was a small miracle to discover Mo-li pictured in Lily’s albums – in photos that even the How descendants had never seen. The photos of the eight sisters, pasted onto the black paper pages of Lily's albums, appear to have been collectible memes as much as personal souvenirs, each taking up nearly a full album page, while most other photos were only a couple of inches in size.

Of course, there are the famous Soong siblings. A notch or two down in fame are seven families featured in York Lo’s 東成西就 (East & West: Chinese Christian Families and Their Roles in Two Centuries of East-West Relations) – among them, the Bao/Bau clan of Mo-li’s mother and uncles who helped co-found the Commercial Press. Lo's book details the seven families’ interconnections and descendants, with passing mention of Han Liang and his children.

Also connected to those families, though unrelated to the Huangs until a wedding in the 1960s, was the family of my maternal grandmother, Lily Ho Quon. Born in Hawaii, Lily grew up in Nanking. She was, I believe, acquainted with the How sisters through their aunt (their mother's sister; maiden name "Bau"), whom Lily called "Aunt Kuo". Aunt Kuo had married into the Kuo family and had a niece, Maida Kuo, who would become Lily's lifelong friend. Lily’s photo albums include many photos of Maida, some of Aunt Kuo and also, serendipitously, some of the How sisters. In recent years, as I figured out the identity of Mo-li, it was a small miracle to discover Mo-li pictured in Lily’s albums – in photos that even the How descendants had never seen. The photos of the eight sisters, pasted onto the black paper pages of Lily's albums, appear to have been collectible memes as much as personal souvenirs, each taking up nearly a full album page, while most other photos were only a couple of inches in size.

TANGLED MATCHES

The influence of the Baus and the Hows grew through intermarriage. The details of their marriages, and divorces, besides offering up piquant stories also encapsulate the era’s rapid evolution, and frequent clash, of values. This site has already dissected the quandary of Han Liang’s own separation and remarriage. Here, in brief, are some of the other liaisons of the period that in some way connect back to Han Liang:

|

- There was also the sister of Chang Kia-ngau, the head of the Bank of China who was unable to help Han Liang in 1932 but who would remain a close friend. The Changs were the archetype of pre-modern pre-eminence, scholarly and respected for many generations. In the early 1900s, the family modernized by sending Kia-ngau and another of their eight or so sons to Japan to study. But with far less education, one of the family's daughters Yu-i was literally and intellectually left behind when her husband, Hsu Chih-mo, from another well-placed family, went off to study in the US and then the UK. Hsu, like Hu Shih, chose to write in the new, accessible vernacular style, and revolutionized Chinese poetry under the influence of the likes of Shelley and Keats. The Chinese public was quickly captivated by his romantic literary style and lifestyle. When he divorced Yu-i to pursue another woman, their split played out in the public eye as China’s first modern divorce.

|

- Coda: In the meantime, Hsu's first wife Chang Yu-i had successfully restarted her life, taking charge of the pioneering Shanghai Women’s Savings Bank (note that since neither Hsu nor Lu Xiaoman were up the task, she also ended up taking care of her former in-laws). Hsu added to his mystique by dying tragically in a plane crash while still quite young.

|

Yet whatever shockwaves there were, they subsided soon enough. In 1944, Ruth Kuo was selected to represent China at International Women's Day (hear her speak in this British Pathe newsclip). Eventually settling in the US, Ruth became something of a mentor to Han Ho's daughter, Mary, and in the photo below, we see Han Liang, Ruth and PW Kuo at Mary's wedding in Philadelphia in 1955:

- The erudite Hu Shih who Han Liang knew at Columbia, was perhaps unique among the maritally dissatisfied movers and shakers of his time. He never abandoned his uneducated village wife, despite a long-standing relationship, intellectual and amorous, with Clifford Williams, a woman he met while studying in the US.