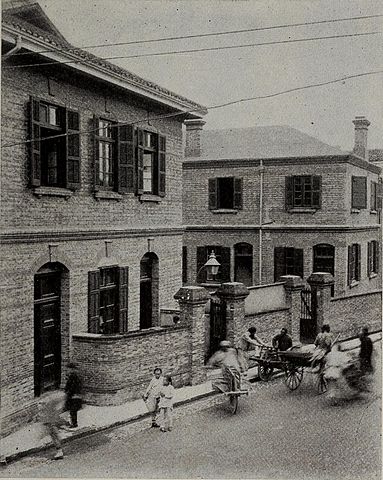

St. Elizabeth's Hospital

c. 1926-1933

After Tsunghua, whether by choice or happenstance, Zing Wei’s life took a sharp turn in a new direction when she made her way to Shanghai. Did she proceed directly from Tsunghua in Suzhou, or return to the Sun home in Wuxi for a time? That she ended up in the big city some 80 miles further east at the end of the train line is hardly a surprise. But how she chose or was guided to the profession of nursing or to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital will probably never be known.

St. Elizabeth’s (廣仁醫院 Guangren Yiyuan), like the better known St. Luke’s (同仁醫院 Tongren Yiyuan), was a teaching hospital of the prestigious St. John’s University (聖約翰大學 Sheng Yuehan Daxue). All three institutions had been started by the American Episcopal Church Mission (美國聖公會 Meiguo Shenggong Hui) during the latter half of the 19th century.

St. Elizabeth’s (廣仁醫院 Guangren Yiyuan), like the better known St. Luke’s (同仁醫院 Tongren Yiyuan), was a teaching hospital of the prestigious St. John’s University (聖約翰大學 Sheng Yuehan Daxue). All three institutions had been started by the American Episcopal Church Mission (美國聖公會 Meiguo Shenggong Hui) during the latter half of the 19th century.

Under the direction of Dr. Marie Haslep, St. Elizabeth’s had begun life in 1890 as the women’s ward of St. Luke’s, which dated from 1866. At least initially, a major sector of patients was “slave girls” (丫頭 yatou, or 妹仔 meizai), such as the clever Jin Mei hired by Han Liang's family to keep his mother company. The church was proud of its efforts to help “this pitiful and neglected class...composed of children who are purchased as infants from poor parents and are brought up either to become servants in wealthy families, or for immoral purposes, or to lead the wretched lives of concubines.” Such were the common fates of girls without Zing Wei’s advantage of an education or, even worse, sold by families who could not care for them.

In 1899, a Mrs. Winslow, the wife of a US army commander, had seen the need for a separate hospital for women and children while on a visit to Shanghai. She wrote an appeal to college girls in America, to which were added the words of Dr. Mary Gates, who ran the ward for four years until 1900. The appeal would have come during the time of the Second Great Awakening and Student Volunteer Movement, when American college students were at a peak of fervor to demonstrate their social commitment to the needy around the world. Funds were raised through the American Episcopal Church’s “Women’s Auxiliary”, and in 1903 the women’s ward was finally spun off as a hospital in its own right.

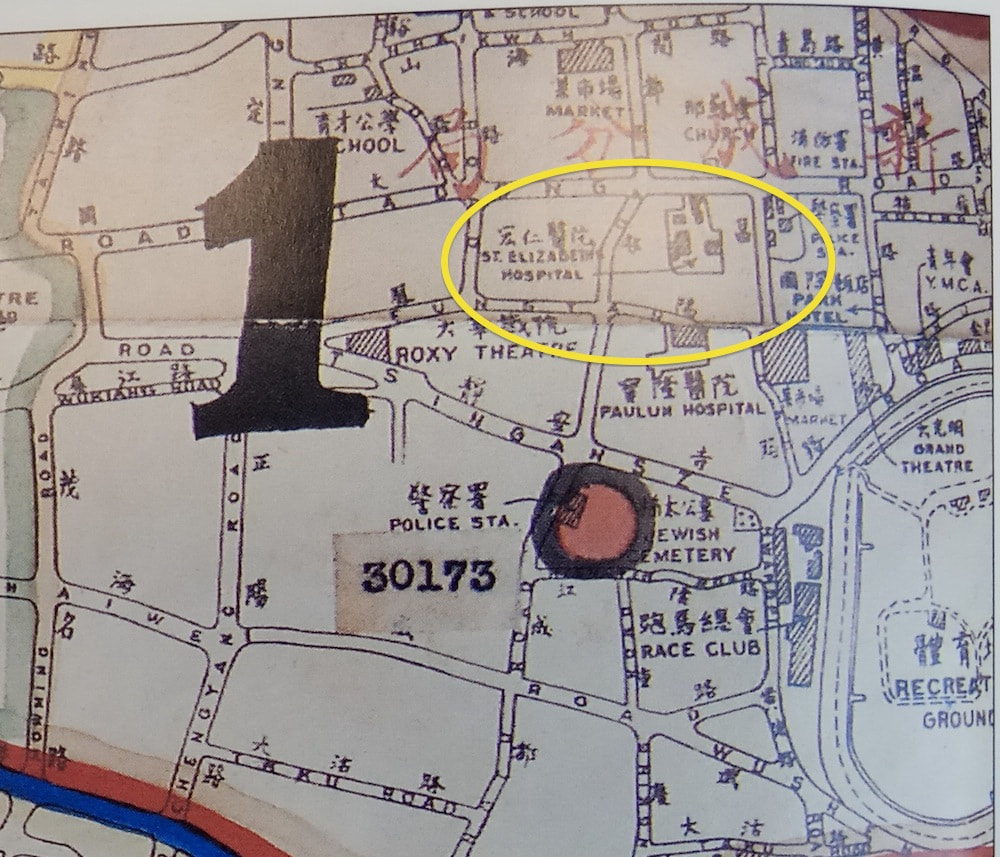

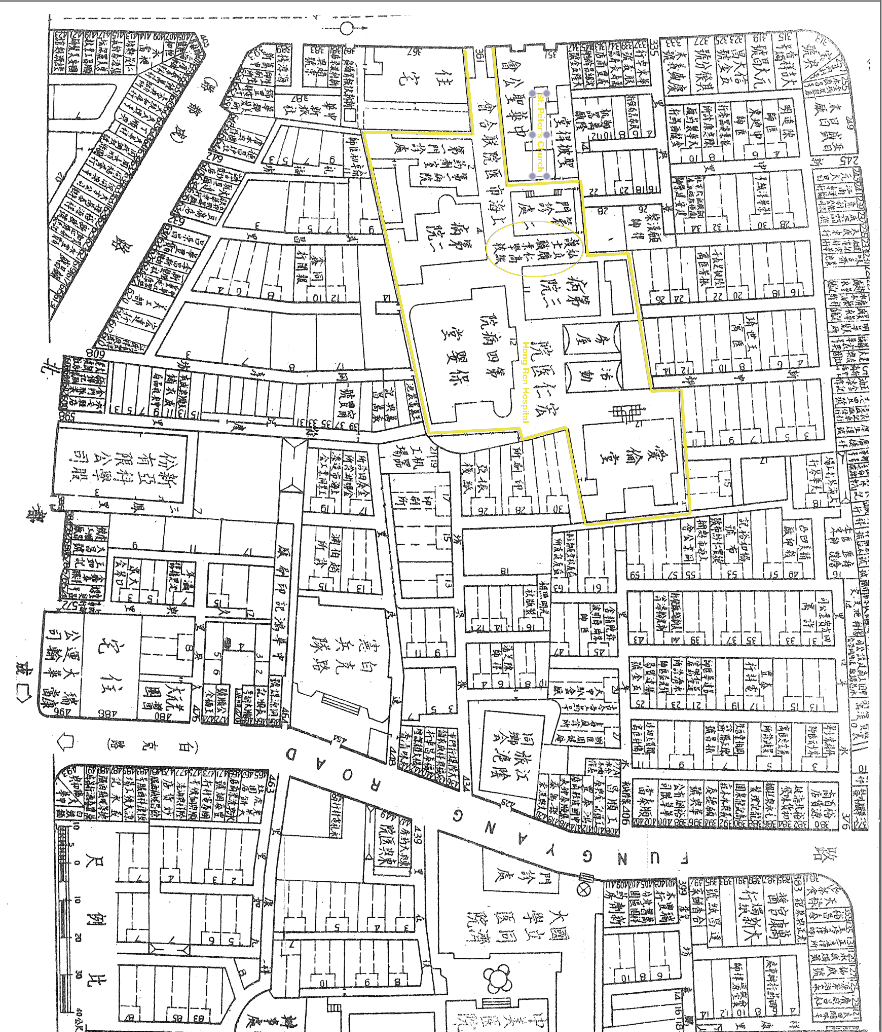

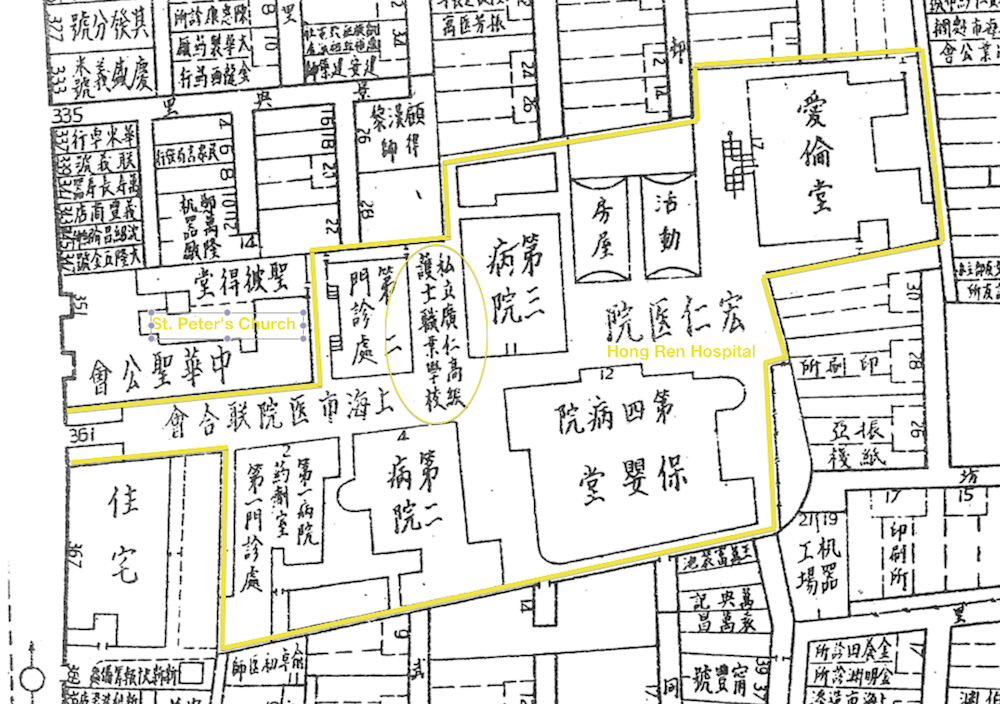

In 1905, a building was erected in the Sinza area (新閘 Xinzha) of Shanghai’s International Settlement, at 361 Avenue Road (愛文義路Aiwenni Lu, now 北京西路 Beijing Xi Lu). The site was within or immediately adjacent to the precinct of St. Peter's Church, which would soon spin off from the American Episcopal Church to become a self-funding Chinese-run parish.

In 1914, St. Elizabeth’s started its nursing program and a burgeoning Nurses’ Association of China also held its fifth national convention in Shanghai. At that gathering, a formal Chinese term for “nurse” was adopted, marking the coming of age of the profession. The term “hushi” (護士) implied a trained professional caregiver. The honor of selecting from a slate of options for the term was given to Elsie Mow Fung Chung, a 1909 graduate of Guy’s Hospital in London and China’s first overseas trained nurse.

If general records are correct, Zing Wei became one of 170 students that St. Elizabeth’s graduated over a period of years. By Zing Wei's time, the medical field had greatly advanced since a young ZF How – Mo-li How's father – served as a nursing trainee before launching his printing empire. Back then, the function of nurses, sometimes called “kanhu“ (看護), was more that of orderly than of nurse, and candidates were typically male and connected to the church.

If general records are correct, Zing Wei became one of 170 students that St. Elizabeth’s graduated over a period of years. By Zing Wei's time, the medical field had greatly advanced since a young ZF How – Mo-li How's father – served as a nursing trainee before launching his printing empire. Back then, the function of nurses, sometimes called “kanhu“ (看護), was more that of orderly than of nurse, and candidates were typically male and connected to the church.

Medical missionary work in China dated back to 1834, when Presbyterian Peter Parker, a fresh graduate of Yale’s schools of divinity and medicine, arrived in Guangzhou. In 1879, the Canton Hospital he had founded admitted China’s first two female students. By the 1930s, one in ten doctors being trained was female – a rate similar to or perhaps even higher than the US.

In 1884, the field of nursing opened up with the arrival in Shanghai of Elizabeth McKechnie, who had been trained at the Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Over the next quarter-century, nursing schools proliferated. The field developed in close parallel to the field of nursing in the US. Nina Gage, a Wellesley graduate and registered nurse from New York’s Roosevelt Hospital, was part of second generation of nurses who did much to raise the stature of the profession and establish its respectability for educated women. She started a nurses’ training program in 1910 as part of Yale’s medical mission in Changsha. She was also first president of the Nurses’ Association of China.

By the 1930s, the Nurses' Association claimed nearly 6,000 members, and China had some 500 hospitals – about half missionary-run, with approximately eight mission-run medical schools. Zing Wei herself would have been one of approximately 1,800 Chinese nurses, 600 Chinese doctors and 300 foreign doctors employed specifically by church-led organizations.

In 1936, by which time Zing Wei would be a mother of three, it was estimated that St. Elizabeth’s had treated a total of 20,000 outpatients and 5,000 inpatients and delivered 1,400 babies – although Zing Wei is not known to have given birth to any of her children at her alma mater. In 1939, the hospital's facilities would be expanded, leading to the new name of “Hongren Yiyuan” (宏仁醫院). In 1952, it became the Shanghai Thoracic Hospital (胸科醫院 Xiongke Yiyuan).

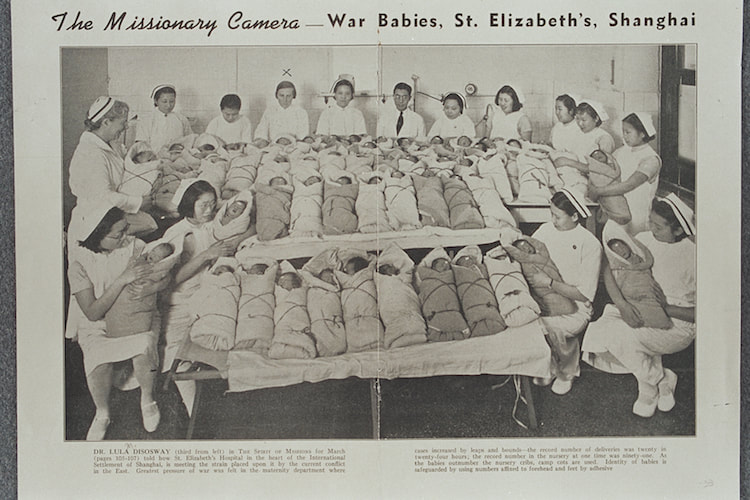

St. Elizabeth's in March 1936, about three years after Zing Wei had left, giving an indication of what her work environment may have been like. War is blamed for the boom of babies, who are bedded on cots due to a lack of cribs and identified by small labels on their foreheads ("The Spirit of Missions", Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University)

|

CHINA'S FIRST WOMEN DOCTORS

Drs. Mary Stone (石美玉 Shi Meiyu, 1873-1954) and Ida Kahn (康成 Kang Cheng,1873-1931) were among the first overseas trained doctors, male or female. Both received medical degrees from the University of Michigan in 1896, making them the university’s first Asian graduates some fifteen years before Boxer Indemnity scholars such as Han Liang and other large groups of Chinese students arrived. The medical profession had evolved rapidly since Dr. Peter Parker introduced Western medicine to China in 1834. Proving particularly successful in treating eye diseases and tumors, Parker and his followers soon had thousands of patients. Taboos about gender roles meant that the first nurses in China tended to be male, as well as church-affiliated. But this also meant that the advent of Western medicine quickly led to the training of both female nurses and female doctors in order to better attend to female patients. By 1901, Kwangtung Medical School or Hackett Medical College was started just for women. |

SOURCES

|