Provincial Capital

Foochow's "Anglo-Chinese College", 1908-1910

In 1908, three years after his father’s death, Han Liang was sixteen or seventeen years old and headed to Foochow (福州, Fuzhou), the capital of the province 200 miles up the coast. He was going to enroll in Fukien’s most prestigious school, the Anglo-Chinese College (ACC, 鶴齡英華書院 Heling Yinghua Shuyuan). He must have been aware that the move would change his prospects radically. Did he know that he might never really live in Amoy again? Foochow's population was over two million, five times that of Amoy, its dialect completely different. We do not know if he made the multi-day boat journey with strangers or perhaps with his younger brother Han Ho, who is also known to have attended the school.

The College would provide them with a crucial stepping stone, just as some 3,000 other mission schools scattered throughout the country were doing for other young Chinese, both male and female. Within a few years, something like a third of elementary schools in Fukien would be Protestant-run enterprises. For girls and for those living in remote areas, missionaries purveyed an even higher percentage of school places.

The College would provide them with a crucial stepping stone, just as some 3,000 other mission schools scattered throughout the country were doing for other young Chinese, both male and female. Within a few years, something like a third of elementary schools in Fukien would be Protestant-run enterprises. For girls and for those living in remote areas, missionaries purveyed an even higher percentage of school places.

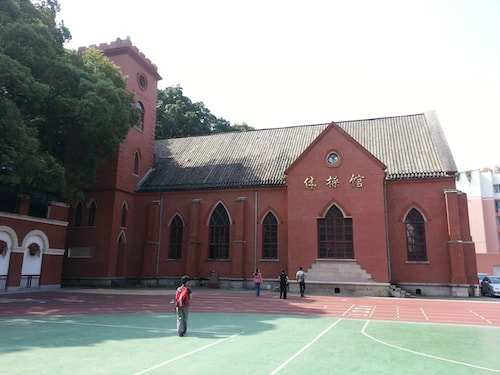

Quite a few schools shared the name “Anglo-Chinese”. There was even one in Amoy on Kulangsu started not long after this one in Foochow, so it must be assumed that the one in Foochow commanded a better reputation. To start with, it claimed to be China’s first school to teach Chinese students in English. Established by American Methodists in February 1881, it was by Han Liang's time the country’s largest mission school with a tuition considerably higher than most. Non-Christians could attend as fee-paying students. Scholarships were available for poorer students and preachers’ sons. It isn’t known whether Yu Koon paid for her sons’ tuition, or whether they earned their places, or how they transitioned from their traditional schooling to this completely new environment.

Like many mission schools, the College did not make conversion compulsory, but one story relates that the Huang brothers were baptized before they enrolled. That would suggest that their education was paid for by the church, but we cannot be sure. Although Han Liang was never known by his children to be a practicing Christian, a half century later when asked to indicate his religious affiliation, he would still call himself a Methodist – perhaps a tip of the hat to the church that gave him his start, perhaps only out of deference to American social custom.

Relative to the scale of the many missions in China, overall conversion rates in China were extremely low. But, interestingly, it was Chinese converts who had made Foochow’s Anglo-Chinese College possible. The Methodist Episcopal Church was known to be more egalitarian than other foreign missions, and as a result, more successful in winning converts. Two of its Chinese preachers had used their equal voting power within the church hierarchy to lobby for the school’s founding, winning out over the concerns of some of their American colleagues that too great a focus on education would sidetrack the mission from evangelism.

Like many mission schools, the College did not make conversion compulsory, but one story relates that the Huang brothers were baptized before they enrolled. That would suggest that their education was paid for by the church, but we cannot be sure. Although Han Liang was never known by his children to be a practicing Christian, a half century later when asked to indicate his religious affiliation, he would still call himself a Methodist – perhaps a tip of the hat to the church that gave him his start, perhaps only out of deference to American social custom.

Relative to the scale of the many missions in China, overall conversion rates in China were extremely low. But, interestingly, it was Chinese converts who had made Foochow’s Anglo-Chinese College possible. The Methodist Episcopal Church was known to be more egalitarian than other foreign missions, and as a result, more successful in winning converts. Two of its Chinese preachers had used their equal voting power within the church hierarchy to lobby for the school’s founding, winning out over the concerns of some of their American colleagues that too great a focus on education would sidetrack the mission from evangelism.

|

A recent convert, Diong Ahok (張鶴齡 Zhang Heling, d. 1890) then contributed ten thousand silver dollars towards the purchase of a building, and his name was incorporated into the Chinese name of the school. A condition of Diong’s gift was that instruction be in English. The school was located on Nantai Island, Foochow's Kulangsu-equivalent foreign enclave.

|

The Huang brothers became part of a student body of three hundred or more. Their teachers included about half a dozen teacher-missionaries from the US. The College offered an eight-year program, roughly equivalent to a junior high school through junior college education. As the story goes, Han Liang studied two grades at a time, completing the equivalent of six years in three (although possibly this story applies to his schooling in Amoy prior to entering the College). Apart from continued study of China’s classical texts in Chinese and bible study in both Chinese and English, the main curriculum was reportedly entirely in English – and as Han Liang's PhD "vita" would note, his study of English only began upon his arrival at the school. Also on offer were geography, history, international law, algebra, trigonometry, botany, chemistry, physics, geology and astronomy – in short, the kind of subjects which forward-looking Chinese believed would help China catch up to the nations of the West and Japan, which had been encroaching on its territory for more than half a century.

|

The College’s first president, Franklin Ohlinger (武林吉 Wu Linji, 1845-1919), originally from Ohio, had ambitious goals for his students: “We do not train men to be cooks and butlers for the foreign merchants, but men who shall be leaders of thought, who shall carry the banner of Christianity and Western Science into every part of these Eighteen Provinces”.

In general, the College’s students did well. By 1917 it would have graduated over 150 students and educated many more. In contrast to the alumni of other schools who were more likely to become educators and preachers, often in rural areas, ACC graduates tended to end up in the major cities pursuing newly available jobs such as those in the foreign consulates or in the customs, salt and postal administrations, which were foreign-run. |

Notable alumni included Lin Sen (林森), a member of the school’s first cohort, who would go on to become China’s titular head of state in 1931; Dr. Sia Tieng Bo (謝天保 Xie Tianbao) from the Class of 1896 who had earned medical and dentistry degrees in the US and who would join the Qing court’s new educational apparatus and also serve as the Chinese consul in North Borneo; as well as the Sycip brothers – Alfonso and Albino Sycip (薛芬士 Xue Fenshi and 薛敏老 Xue Minlao) – Manila-born Fukienese a few years older than the Huang brothers. The brothers would exemplify a new era of overseas Chinese commercial success. Indeed, as will be learned later in this narrative, Albino would give Han Liang his first job and become a lifelong associate.

The Sycips were probably not at the College at the same time as the Huang brothers, but perhaps Han Liang forged other important contacts there. It was during these years that he almost certainly began a long-standing connection with the YMCA movement, which had a strong presence at the school. China’s first YMCA group had been started there in 1885, and in 1907, the year before Han Liang enrolled, ACC alumni played a key role in founding a citywide Foochow YMCA. This new civic body was enthusiastically endorsed by high-ranking government officials and soon had more non-Christian than Christian members. The YMCA aimed to put Christian principles into practice by fostering “a healthy spirit, mind, and body” (德育、智育、體育 deyu, zhiyu, tiyu). This practical approach to social reform suited China perfectly.

While at the College, Han Liang would also have gotten a taste of the more turbulent forms social change could take. ACC students and alumni were at the forefront of many political movements, of which he must have been aware, even if he chose to keep his head down and strictly focus on his studies. In 1905, before Han Liang arrived, 250 College students had participated in a nationwide boycott of American goods, expressing outrage at exclusionary immigration laws and the mistreatment of Chinese in the US. In 1910, while Han Liang was a student, a classmate cut off his queue in a gesture of anti-Qing resistance, allegedly the first man in the province to do so. Chiang Kai-shek had cut his queue in 1906 before going to Japan. While bold, such measures were growing apace.

In 1909, Han Liang was likely to have laid eyes on the history-makers elected to Fukien’s first-ever Provincial Assembly. The assemblies were part of a nationwide experiment in representative government by the Qing court. Together the Methodist Church and YMCA hosted a reception for Assembly members that was partially held on College grounds. One of the youngest and most outspoken members of the new Assembly was an ACC alumnus, Chen Zhilin, who at the same time as graduating from the College in 1903 had also qualified for a juren (舉人) degree in Fukien’s last imperial exams.

Given the breakneck speed at which Han Liang is said to have studied, certainly by the end of 1910, if not earlier, the school must have had Han Liang in its sights as a candidate for a new type of national exam, hastily thrown together for the first time one year before. These new exams would offer a chance to study in America.

The Sycips were probably not at the College at the same time as the Huang brothers, but perhaps Han Liang forged other important contacts there. It was during these years that he almost certainly began a long-standing connection with the YMCA movement, which had a strong presence at the school. China’s first YMCA group had been started there in 1885, and in 1907, the year before Han Liang enrolled, ACC alumni played a key role in founding a citywide Foochow YMCA. This new civic body was enthusiastically endorsed by high-ranking government officials and soon had more non-Christian than Christian members. The YMCA aimed to put Christian principles into practice by fostering “a healthy spirit, mind, and body” (德育、智育、體育 deyu, zhiyu, tiyu). This practical approach to social reform suited China perfectly.

While at the College, Han Liang would also have gotten a taste of the more turbulent forms social change could take. ACC students and alumni were at the forefront of many political movements, of which he must have been aware, even if he chose to keep his head down and strictly focus on his studies. In 1905, before Han Liang arrived, 250 College students had participated in a nationwide boycott of American goods, expressing outrage at exclusionary immigration laws and the mistreatment of Chinese in the US. In 1910, while Han Liang was a student, a classmate cut off his queue in a gesture of anti-Qing resistance, allegedly the first man in the province to do so. Chiang Kai-shek had cut his queue in 1906 before going to Japan. While bold, such measures were growing apace.

In 1909, Han Liang was likely to have laid eyes on the history-makers elected to Fukien’s first-ever Provincial Assembly. The assemblies were part of a nationwide experiment in representative government by the Qing court. Together the Methodist Church and YMCA hosted a reception for Assembly members that was partially held on College grounds. One of the youngest and most outspoken members of the new Assembly was an ACC alumnus, Chen Zhilin, who at the same time as graduating from the College in 1903 had also qualified for a juren (舉人) degree in Fukien’s last imperial exams.

Given the breakneck speed at which Han Liang is said to have studied, certainly by the end of 1910, if not earlier, the school must have had Han Liang in its sights as a candidate for a new type of national exam, hastily thrown together for the first time one year before. These new exams would offer a chance to study in America.

|

Banner caption: Foochow in 1906 or 1907, one or two years before Han Liang arrived (https://www.hpcbristol.net, image #sw13-134)

|

|

SOURCES

|

This page is based extensively on information in:

|

Affiliation as a Methodist:

Fukien's Provincial Assembly is mentioned in:

|