Treaty Port City

Life in Amoy, c. 1891-1908

Yu Koon and her sons lived in the coastal city known today as Xiamen (廈門) in Fujian Province (福建省). That is how the place names are written in standard Mandarin pinyin today. But in the local dialect they spoke, those same characters for city and province were pronounced “Amoy” and "Fukien" or “Hokkien”. Amoy, Fukienese and Hokkien thus became names for their dialect.

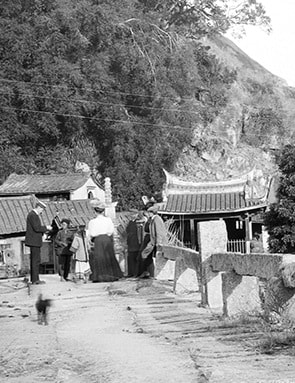

Amoy was a small island off of China’s southeast coast – about eight miles across and twenty-five miles around – somewhat larger than Hong Kong island and more rugged. The landscape was striking: a narrow shoreline rising sharply into hills of more than a thousand feet, strewn everywhere with massive boulders. These Stonehenge-sized boulders stood in clumps or singly – like Sunlight Rock (日光岩 Riguang Yan) which overlooked Amoy’s harbor, or Rocking Stone (風動石 Shengdong Shi), which balanced on one end and actually swayed in the wind. They were a hindrance to farming and a constant reminder of forces greater than man.

Amoy was a small island off of China’s southeast coast – about eight miles across and twenty-five miles around – somewhat larger than Hong Kong island and more rugged. The landscape was striking: a narrow shoreline rising sharply into hills of more than a thousand feet, strewn everywhere with massive boulders. These Stonehenge-sized boulders stood in clumps or singly – like Sunlight Rock (日光岩 Riguang Yan) which overlooked Amoy’s harbor, or Rocking Stone (風動石 Shengdong Shi), which balanced on one end and actually swayed in the wind. They were a hindrance to farming and a constant reminder of forces greater than man.

When a citizen of Amoy died, he or she was buried in these same rocky hills – although Ye-Tau appears not to have been. A good burial spot was ideally selected much as one would choose a site for a house, with high ground to one’s back and a vista of water ahead. Proper burial was so important that Huang family records are mainly a log of compass coordinates for final resting spots, along with precise dates and times of birth and death, but without details of the lives led.

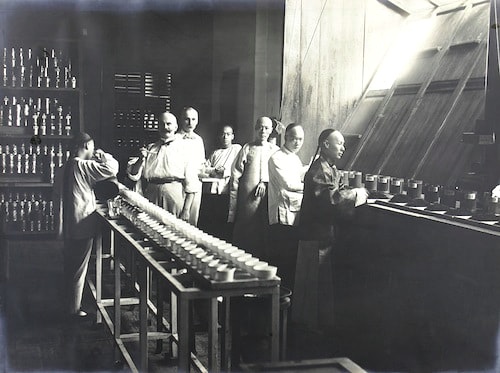

We have to imagine that Han Liang and Han Ho looked much like the young men in photos of Chinese workers imported to build the US railroads in the 19th century – not necessarily because they were poor but because such clothing was, more or less, what all Chinese of the time wore: loose-fitting tunics and trousers and cloth shoes. How clean or worn, plain or luxurious, the fabrics would have depended on exactly where on the socio-economic ladder they fell. They would have worn their hair in a "queue" or long, braided pigtail accompanied by shaved foreheads – a custom started in the 17th century when the northern Manchu peoples conquered China to rule as the Qing dynasty (清, sometimes written "Ching"). Young men a bit older than the Huang boys might also have a worn a head cloth that could double as a sash.

Yu Koon would have gone about collecting rent, or conducting whatever modest business it was, with bound feet. This was a much older Chinese custom, which the Manchus had tried unsuccessfully to outlaw and which Manchu women were forbidden to adopt. By this time period, residents of Amoy were likely to have been aware of growing appeals by social reformers and Christian missionaries to end this practice, which to many epitomized Chinese backwardness. But one imagines such calls would have been meaningless to Yu Koon, who simply accepted the state of her feet as the desirable norm for a woman. Following local custom, she likely wore a linen tunic, perhaps trimmed with a wide decorative border, a matching headband, and trousers of brown or black lacquered cotton.

Given Yu Koon's need for frugality, we assume the family frequently ate sweet potatoes. Rice was cultivated in Amoy but because land was rocky and scarce, the humble, hardy sweet potato had become the staple food. It could be dried for consumption year round and shredded to make a kind of rice substitute.

Beyond its coast, Fukien was nearly impassable mountain forest, which cut it off from the rest of China. Some of the country's most famous tea was and is still grown in the "Bohea" mountains (武夷山 Wuyi Shan, "Boo-hee" in Hokkien) that marked the inland edge of the province. But generally agriculture in Fukien's rugged terrain was difficult, and for safety’s sake, inland Fukienese lived in giant roundhouses that functioned as self-contained villages. No wonder that for centuries it had often made more sense for young Fukienese to try their luck across the seas, engaging in trade with Southeast Asia or destinations beyond. The imperial court was ambivalent about overseas contact, but even when it banned maritime commerce outright, enterprising Fukienese merchants still found ways to trade or smuggle goods.

We have to imagine that Han Liang and Han Ho looked much like the young men in photos of Chinese workers imported to build the US railroads in the 19th century – not necessarily because they were poor but because such clothing was, more or less, what all Chinese of the time wore: loose-fitting tunics and trousers and cloth shoes. How clean or worn, plain or luxurious, the fabrics would have depended on exactly where on the socio-economic ladder they fell. They would have worn their hair in a "queue" or long, braided pigtail accompanied by shaved foreheads – a custom started in the 17th century when the northern Manchu peoples conquered China to rule as the Qing dynasty (清, sometimes written "Ching"). Young men a bit older than the Huang boys might also have a worn a head cloth that could double as a sash.

Yu Koon would have gone about collecting rent, or conducting whatever modest business it was, with bound feet. This was a much older Chinese custom, which the Manchus had tried unsuccessfully to outlaw and which Manchu women were forbidden to adopt. By this time period, residents of Amoy were likely to have been aware of growing appeals by social reformers and Christian missionaries to end this practice, which to many epitomized Chinese backwardness. But one imagines such calls would have been meaningless to Yu Koon, who simply accepted the state of her feet as the desirable norm for a woman. Following local custom, she likely wore a linen tunic, perhaps trimmed with a wide decorative border, a matching headband, and trousers of brown or black lacquered cotton.

Given Yu Koon's need for frugality, we assume the family frequently ate sweet potatoes. Rice was cultivated in Amoy but because land was rocky and scarce, the humble, hardy sweet potato had become the staple food. It could be dried for consumption year round and shredded to make a kind of rice substitute.

Beyond its coast, Fukien was nearly impassable mountain forest, which cut it off from the rest of China. Some of the country's most famous tea was and is still grown in the "Bohea" mountains (武夷山 Wuyi Shan, "Boo-hee" in Hokkien) that marked the inland edge of the province. But generally agriculture in Fukien's rugged terrain was difficult, and for safety’s sake, inland Fukienese lived in giant roundhouses that functioned as self-contained villages. No wonder that for centuries it had often made more sense for young Fukienese to try their luck across the seas, engaging in trade with Southeast Asia or destinations beyond. The imperial court was ambivalent about overseas contact, but even when it banned maritime commerce outright, enterprising Fukienese merchants still found ways to trade or smuggle goods.

|

In such conditions, Fukien's great gift to the world became tea – and not just the beverage, but also its many names. The word “tea” and its European-language variants come from “te”, the local pronunciation for the character “茶” (while Indian and Middle Eastern names like "chai" derive from the Cantonese and Mandarin “cha”). From Fukien came prized varieties such as "Bohea", "Oolong" (烏龍 Wulong; "dark dragon"), "Lapsang Souchong" (立山小種 Lishan Xiaozhong), and the tea that the American patriots threw into Boston Harbor.

World renowned though Fukien tea was, by Han Liang's time, the city's tea trade was in decline, outstripped by exports from nearby Taiwan. Under Japanese control since 1895, the island was home to vast plantations of both tea and sugarcane. |

Amoy was a relative latecomer as a Fukien port city. Changchow, Chuanchow and Foochow were the older harbors that had welcomed 10th century Arab traders, earned fame in Marco Polo's tales of the 1200s, and served as jumping off points for some of the Ming dynasty missions of Admiral Cheng Ho (鄭和 Zheng He). Located at the mouths of rivers, these cities had served as the conduits that made China famous for tea and oranges, among other valued Chinese goods. Over the course of a millennium, Fukienese merchants became adept at aggregating not only local produce but also silk, porcelain and other products from around the country.

Then, as trade became not just regional but global, Amoy's advantage as a natural deep-water port grew in importance. Large ships could dock right at the city's edge. From the mid-1500s, Amoy became a key link in a supply chain that brought Chinese luxury goods to Europe in exchange for new world silver from Spanish colonies in Bolivia and Mexico. When silver coins became essential for the functioning of their economy, China's emperors became more tolerant of trade – and in fact, in Han Liang and Han Ho's time, Mexican dollars were still common currency in China.

For two and a half centuries, a large community of Amoy merchants helped make Manila a critical transshipment point for Spanish galleons. Chinatowns of Fukienese traders could be found throughout Southeast Asia, and it became common for young men to make at least temporary homes in various parts of the region. As will be seen, in line with this pattern, Han Liang himself would at various points reside in Manila, while one of his cousins – Been-Sa's oldest surviving son – would settle permanently in Singapore.

The Amoy that Han Liang knew represented a shift in these long-standing trade arrangements. Eventually the supply of New World silver dried up but not so the demand for tea and other Chinese goods, and British merchants began to pay for their China purchases with opium from their colonies in India. Trade and opium became such sticking points between the two nations that England instigated war against the Qing court. The Opium Wars were mainly waged around Canton, but in Han Liang's time, there might still have been elderly residents of Amoy who remembered when the British fleet sailed into the harbor in August 1841 and 8,000 Chinese soldiers and a couple dozen war junks held their own against the world's mightiest navy. The city survived the immediate naval onslaught, but ultimately fell to a land attack and the larger British defeat of the Chinese. In 1842, the Qing court signed the Treaty of Nanking, which granted the British trading rights in Canton, Amoy and three other Chinese "treaty port" cities (Foochow, Shanghai and Ningpo), as well as permanent ownership of Hong Kong.

Then, as trade became not just regional but global, Amoy's advantage as a natural deep-water port grew in importance. Large ships could dock right at the city's edge. From the mid-1500s, Amoy became a key link in a supply chain that brought Chinese luxury goods to Europe in exchange for new world silver from Spanish colonies in Bolivia and Mexico. When silver coins became essential for the functioning of their economy, China's emperors became more tolerant of trade – and in fact, in Han Liang and Han Ho's time, Mexican dollars were still common currency in China.

For two and a half centuries, a large community of Amoy merchants helped make Manila a critical transshipment point for Spanish galleons. Chinatowns of Fukienese traders could be found throughout Southeast Asia, and it became common for young men to make at least temporary homes in various parts of the region. As will be seen, in line with this pattern, Han Liang himself would at various points reside in Manila, while one of his cousins – Been-Sa's oldest surviving son – would settle permanently in Singapore.

The Amoy that Han Liang knew represented a shift in these long-standing trade arrangements. Eventually the supply of New World silver dried up but not so the demand for tea and other Chinese goods, and British merchants began to pay for their China purchases with opium from their colonies in India. Trade and opium became such sticking points between the two nations that England instigated war against the Qing court. The Opium Wars were mainly waged around Canton, but in Han Liang's time, there might still have been elderly residents of Amoy who remembered when the British fleet sailed into the harbor in August 1841 and 8,000 Chinese soldiers and a couple dozen war junks held their own against the world's mightiest navy. The city survived the immediate naval onslaught, but ultimately fell to a land attack and the larger British defeat of the Chinese. In 1842, the Qing court signed the Treaty of Nanking, which granted the British trading rights in Canton, Amoy and three other Chinese "treaty port" cities (Foochow, Shanghai and Ningpo), as well as permanent ownership of Hong Kong.

|

Over the next few decades, other nations signed their own treaties, granting them sovereignty over pockets of China and ushering in what would be a century of Chinese subservience to the world's outward-looking powers. And along with the traders soon came Christian missionaries.

By the time Han Liang was four, tiny Japan which China had traditionally viewed as its inferior had undertaken several decades of modernization and sought to join the Western powers on the world stage. It too swept in on China and easily defeated it militarily, taking control in 1895 of the Korean peninsula and port cities in the north, as well as the vast island of Taiwan that lay less than 200 miles off the Fukien coast. During Han Liang's youth, Japanese, Britons, Americans, Germans and other westerners would have been a daily sight in his hometown. |

|

Banner caption: Amoy, c. 1880s (https://www.hpcbristol.net, image #os01-025)

|

|

SOURCES

|

|