Imperial City

Office of the China Educational Mission to America, 1911

In early 1911, Han Liang set out on the most demanding journey of his life.

He was headed to Peking to test his mettle in one of the contests that had replaced the old imperial examinations: the exams to qualify for a Boxer Indemnity scholarship (庚子賠款獎學金 Gengzi Peikuan Jiangxuejin) to go to the United States.

Two groups of students had already been sent in 1909 and 1910, albeit in haste. Now going into a third year, the selection process was bedding down, but interest also growing. After all, the old exam system had been abolished in 1905, but that was two years after the last exams were actually held at the provincial level. There was huge pent-up demand for an officially sanctioned route for advancement. The current year's pool of contestants was also going to be much larger because there was a chance not only to win an immediate overseas scholarship, but also to vie for a place at a new school that would prepare students as young as thirteen or fourteen for study in the US in a few years' time. The new school was slated to open on the grounds of what had been the Tsinghua royal gardens (清華花園 Tsinghua Huayuan).

After the completion of the previous summer's exams, appeals had immediately gone out for the next year. Local level exams were to be run to select candidates for further testing in Peking in early 1911. The number of places available was supposed to be proportional to a province's share of Boxer Indemnity expenses. A rich province like Kwangtung (廣東Guangdong) in the South or Kiangsu (江蘇 Jiangsu) in the East might be allocated twenty or more slots, while a remote province like Sinkiang (新疆 Xinjiang) in the far West might only get two. But in fact it was proving difficult to identify sufficiently qualified students to fill all 100 scholarship places – hence the decision to open a preparatory school.

The branch of the Qing court with Han Liang's fate in its hands was the Office of the China Educational Mission to America (OCEMA, 遊美學務處 Youmei Xuewuchu). The OCEMA was set up in 1909 after the US decided that it would return part of the Boxer Rebellion war reparations owed to it by China in the form of scholarships for Chinese students. In 1898, anti-foreign rebels known as the “Righteous Fists of Harmony” or “Boxers” had attacked Christian missions and embassies in northern China. In dispersed locations, a couple hundred foreign missionaries and thousands of Chinese Christians were killed. In 1900, the hostilities escalated into a 55-day siege of Peking’s Legation Quarter. The siege only ended when an Eight-Nation Alliance positioned gunships along China’s coast and sent in 20,000 troops.

In the aftermath, these eight foreign powers, including Japan, levied reparations on the weak Qing court equivalent to billions of dollars at today's values and more than double the court’s annual income – payable with interest over a period of forty years. Then in 1904, the US opened a dialogue to arrange the return of at least part of this crippling sum.

There were forward-looking minds on both sides who had the vision to apply the funds towards education. However, negotiations dragged on. After the Chinese anti-American boycott of 1905, in which some of Han Liang's ACC schoolmates were involved, President Theodore Roosevelt and others were more determined than ever to see relations improved. Still, an agreement was only signed in October 1908 and it was not until the following July that a Chinese Foreign Ministry official, Tang Guo'an (唐國安), who had himself studied in the US, was appointed to head the new OCEMA. By then, time was short to select students for the 1909 fall term. Telegrams were hurriedly sent to every province to appeal for applicants. Thus the earlier appeal for the 1911 cohort.

It's assumed that the hard-working Han Liang had with the support of a well-established school such as ACC already passed a local qualifying exam, but possibly Han Liang was headed to Peking to try his chances in the open competition. Given the difficulty in finding students with the right kind of preparation, the reality was that students like Han Liang from missionary and other modern schools had a big leg up, and ultimately nearly two-thirds of those chosen came from the Shanghai-Nanking area.

Han Liang's dissertation "vita" says he arrived in Peking in January. We take that to mean some time in the first month of the lunar calendar. In 1911, the lunar new year's day fell on January 30. Registration for the open exam was scheduled from February 4 to 8. The 184 candidates who had already qualified at the provincial level were asked to report to Peking by February 18. Either way, Han Liang would not have had much time to dally over new year's celebrations, whether departing from Foochow, or from Amoy after some holiday time with his mother and brother.

Getting to Peking from Fukien would have been arduous, involving a boat or two and perhaps Han Liang's first train ride – although the rail lines that would have been most helpful to his journey would not go into service until the following year. Only one thing is certain: Peking’s winter weather would have been bitter for a first-time traveler from the south.

The open exams ran from February 12 to 14. Over 1000 candidates took part. Given the high stakes, there were many stories of boys and young men pretending to be older or younger to have this chance. In the end, since there was only one test paper, older candidates did have an edge. Out of the 1000, 116 students were selected outright and another twenty-five wait-listed.

By mid-February, by whatever means he had qualified, Han Liang was now one of nearly 300+ who would take a second round of exams on March 5-6. These exams appear to have been somewhat less high-stakes, intended to verify the first-round results, rather than to cull. The exams included writing an essay in Chinese on one of five topics as diverse as "Changes in Literary Styles from Ancient to Modern Times" or "Public Parks & Sanitation". Perhaps one's choice of topic was a litmus test of one's modernity. There were also exam papers on history, geography and math, and two English tests – one on grammar and another that involved writing from memory.

Han Liang made it through. His next order of business was to report to the new Tsinghua campus before the end of March.

He was headed to Peking to test his mettle in one of the contests that had replaced the old imperial examinations: the exams to qualify for a Boxer Indemnity scholarship (庚子賠款獎學金 Gengzi Peikuan Jiangxuejin) to go to the United States.

Two groups of students had already been sent in 1909 and 1910, albeit in haste. Now going into a third year, the selection process was bedding down, but interest also growing. After all, the old exam system had been abolished in 1905, but that was two years after the last exams were actually held at the provincial level. There was huge pent-up demand for an officially sanctioned route for advancement. The current year's pool of contestants was also going to be much larger because there was a chance not only to win an immediate overseas scholarship, but also to vie for a place at a new school that would prepare students as young as thirteen or fourteen for study in the US in a few years' time. The new school was slated to open on the grounds of what had been the Tsinghua royal gardens (清華花園 Tsinghua Huayuan).

After the completion of the previous summer's exams, appeals had immediately gone out for the next year. Local level exams were to be run to select candidates for further testing in Peking in early 1911. The number of places available was supposed to be proportional to a province's share of Boxer Indemnity expenses. A rich province like Kwangtung (廣東Guangdong) in the South or Kiangsu (江蘇 Jiangsu) in the East might be allocated twenty or more slots, while a remote province like Sinkiang (新疆 Xinjiang) in the far West might only get two. But in fact it was proving difficult to identify sufficiently qualified students to fill all 100 scholarship places – hence the decision to open a preparatory school.

The branch of the Qing court with Han Liang's fate in its hands was the Office of the China Educational Mission to America (OCEMA, 遊美學務處 Youmei Xuewuchu). The OCEMA was set up in 1909 after the US decided that it would return part of the Boxer Rebellion war reparations owed to it by China in the form of scholarships for Chinese students. In 1898, anti-foreign rebels known as the “Righteous Fists of Harmony” or “Boxers” had attacked Christian missions and embassies in northern China. In dispersed locations, a couple hundred foreign missionaries and thousands of Chinese Christians were killed. In 1900, the hostilities escalated into a 55-day siege of Peking’s Legation Quarter. The siege only ended when an Eight-Nation Alliance positioned gunships along China’s coast and sent in 20,000 troops.

In the aftermath, these eight foreign powers, including Japan, levied reparations on the weak Qing court equivalent to billions of dollars at today's values and more than double the court’s annual income – payable with interest over a period of forty years. Then in 1904, the US opened a dialogue to arrange the return of at least part of this crippling sum.

There were forward-looking minds on both sides who had the vision to apply the funds towards education. However, negotiations dragged on. After the Chinese anti-American boycott of 1905, in which some of Han Liang's ACC schoolmates were involved, President Theodore Roosevelt and others were more determined than ever to see relations improved. Still, an agreement was only signed in October 1908 and it was not until the following July that a Chinese Foreign Ministry official, Tang Guo'an (唐國安), who had himself studied in the US, was appointed to head the new OCEMA. By then, time was short to select students for the 1909 fall term. Telegrams were hurriedly sent to every province to appeal for applicants. Thus the earlier appeal for the 1911 cohort.

It's assumed that the hard-working Han Liang had with the support of a well-established school such as ACC already passed a local qualifying exam, but possibly Han Liang was headed to Peking to try his chances in the open competition. Given the difficulty in finding students with the right kind of preparation, the reality was that students like Han Liang from missionary and other modern schools had a big leg up, and ultimately nearly two-thirds of those chosen came from the Shanghai-Nanking area.

Han Liang's dissertation "vita" says he arrived in Peking in January. We take that to mean some time in the first month of the lunar calendar. In 1911, the lunar new year's day fell on January 30. Registration for the open exam was scheduled from February 4 to 8. The 184 candidates who had already qualified at the provincial level were asked to report to Peking by February 18. Either way, Han Liang would not have had much time to dally over new year's celebrations, whether departing from Foochow, or from Amoy after some holiday time with his mother and brother.

Getting to Peking from Fukien would have been arduous, involving a boat or two and perhaps Han Liang's first train ride – although the rail lines that would have been most helpful to his journey would not go into service until the following year. Only one thing is certain: Peking’s winter weather would have been bitter for a first-time traveler from the south.

The open exams ran from February 12 to 14. Over 1000 candidates took part. Given the high stakes, there were many stories of boys and young men pretending to be older or younger to have this chance. In the end, since there was only one test paper, older candidates did have an edge. Out of the 1000, 116 students were selected outright and another twenty-five wait-listed.

By mid-February, by whatever means he had qualified, Han Liang was now one of nearly 300+ who would take a second round of exams on March 5-6. These exams appear to have been somewhat less high-stakes, intended to verify the first-round results, rather than to cull. The exams included writing an essay in Chinese on one of five topics as diverse as "Changes in Literary Styles from Ancient to Modern Times" or "Public Parks & Sanitation". Perhaps one's choice of topic was a litmus test of one's modernity. There were also exam papers on history, geography and math, and two English tests – one on grammar and another that involved writing from memory.

Han Liang made it through. His next order of business was to report to the new Tsinghua campus before the end of March.

|

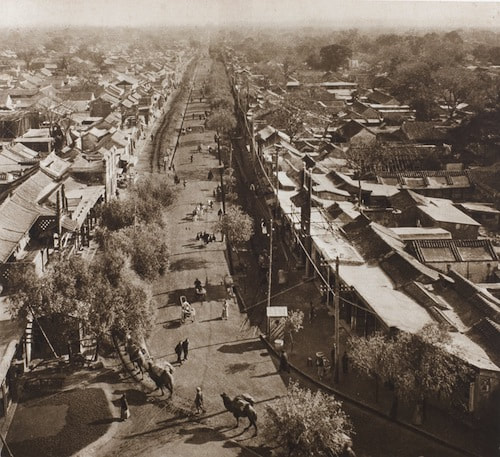

Although it's assumed that Han Liang spent every free moment revising with whatever books and papers he had been able to transport with him, perhaps he stole a little time to get acquainted with this city of emperors. For now they were being housed and examined in the city center, not far from the foreign legation quarter which had been violated during the Boxer Rebellion. Once Tsinghua opened, they would be removed to the city's northern edge.

Peking was a city of endless walls. There were massive walls of grey brick outlining the city limits, human-scaled walls of grey brick that housed private residences and traced a mazy grid of small lanes (胡同 hutong), as well as the unapproachable red stucco walls that signaled the Forbidden City palace grounds. There was in fact little in the way of sightseeing, as nearly everything considered a sight today was then the off-limits preserve of the five-year-old emperor Puyi (溥儀愛新覺羅 Puyi Aixin Jue Luo) and his courtiers. |

|

Nonetheless, every lane and street corner offered clothing, accents and flavors, the likes of which Han Liang had never encountered. With no quay or bund or river, he was truly a fish out of water, a southern lad of nineteen, who despite his book smarts might have gawked to see a camel caravan from the Gobi desert.

SOURCES

|

|