Hong Kong Roots

1937-1942

In Hong Kong, the family expanded from three children to six. May, Peter and Paul were joined by:

Based on Stephen’s age, it’s assumed that the photo at the top of this page was taken in Hong Kong in 1940 when Zing Wei would have been pregnant with Philip.

- Helen or “Sze Mei“ (思梅 Simei), born July 21, 1938, the Year of the Tiger;

- Stephen or “Chung Li” (宗禮 Zongli), born August 3, 1939, the Year of the Rabbit;

- and Philip or “Chung Chih” (宗智 Zongzhi), born October 1, 1940, the Year of the Dragon.

Based on Stephen’s age, it’s assumed that the photo at the top of this page was taken in Hong Kong in 1940 when Zing Wei would have been pregnant with Philip.

Uncle Han Ho’s family returned to Shanghai in 1939. They had lived for two years on Bonham Road, where Mary attended St. Stephen’s Girls’ College, an English-language school. But Han Ho and Peggy wanted their two daughters to learn more Chinese, and in 1939 they felt it was safe enough to return to Shanghai. Mary was about thirteen and Lulu about six.

During these years, all spent on Hong Kong island, none of Han Liang and Zing Wei’s children, all younger than Lulu, would attend any kind of formal schooling.

It’s assumed that at first the family lived on the 2nd Floor of 10 Po Shan Road (寶山道 Bao Shan Dao), the address noted on Helen’s birth certificate. But the house the children remember was at 39 Stubbs Road (司徒拔道39號 Situ Ba Dao 39 Hao). They might have moved there in late 1938 after Helen was born, or in 1939 as their family continued to expand.

During these years, all spent on Hong Kong island, none of Han Liang and Zing Wei’s children, all younger than Lulu, would attend any kind of formal schooling.

It’s assumed that at first the family lived on the 2nd Floor of 10 Po Shan Road (寶山道 Bao Shan Dao), the address noted on Helen’s birth certificate. But the house the children remember was at 39 Stubbs Road (司徒拔道39號 Situ Ba Dao 39 Hao). They might have moved there in late 1938 after Helen was born, or in 1939 as their family continued to expand.

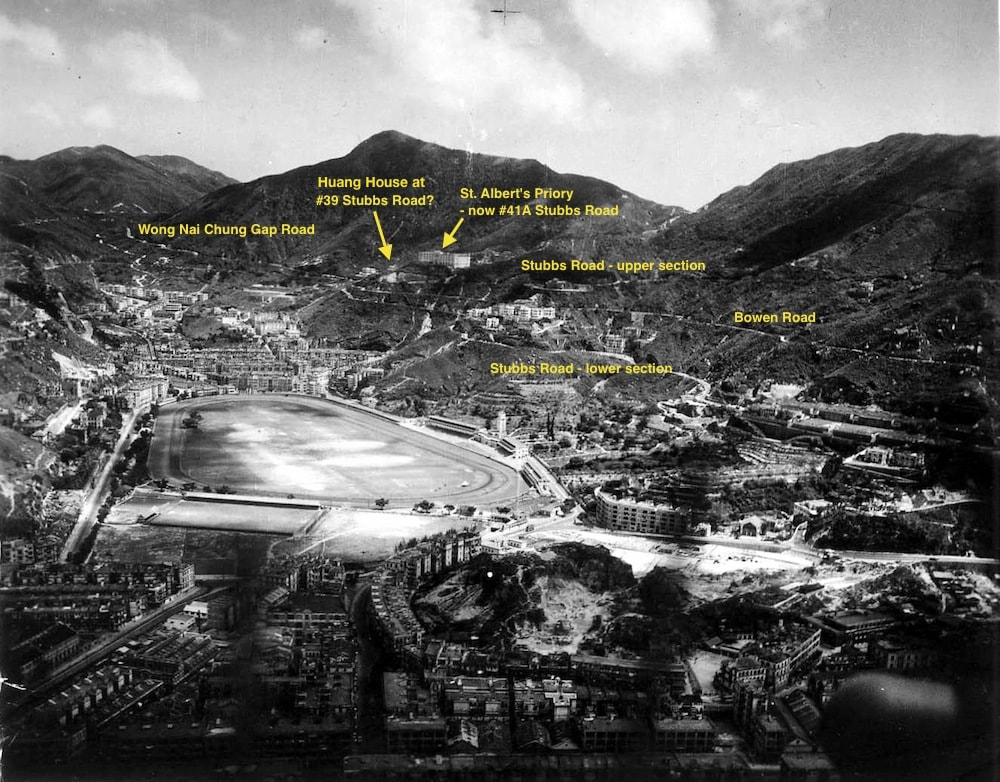

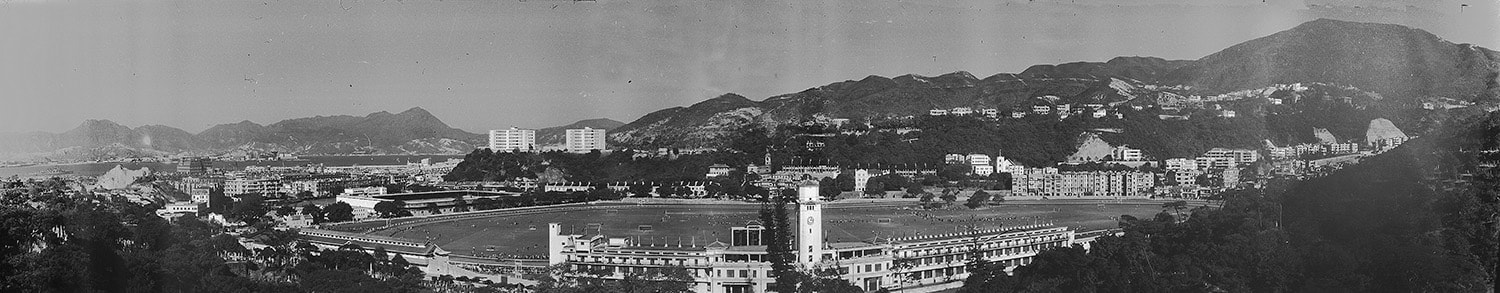

On three levels hugging a hillside, the house looked out over the Happy Valley Racecourse to the harbor beyond. It was on the uphill side of the road, and had a terraced garden big enough to accommodate tennis games, which Han Liang loved – the lines would be chalked out on the grass every day. It also had two living rooms, one furnished entirely in heavy dark wood Chinese furniture and another decorated with gilt Western furnishings. There was also a separate servants’ block detached from the house, where a staff of about fourteen lived. Every child had his or her own amah who would sleep at their bedsides.

Zing Wei recalls that they rented the house from a Jewish family. Old juror records indicate that 39 Stubbs Road was indeed occupied from 1936 to late 1938 or early 1939 by an Albert Raymond, a director of the ED Sassoon textile empire and prominent member of Hong Kong's Jewish community (his and his wife's graves may still be found in the Jewish cemetery in Happy Valley). Prior to the Raymonds, from about 1932, three brothers from Bahrain, surnamed Edgar and also Jewish, lived there. During that time, 39 Stubbs Road was sometimes referred to as “Flowerburn”, suggesting an even earlier Scottish owner or builder.

Zing Wei recalls that they rented the house from a Jewish family. Old juror records indicate that 39 Stubbs Road was indeed occupied from 1936 to late 1938 or early 1939 by an Albert Raymond, a director of the ED Sassoon textile empire and prominent member of Hong Kong's Jewish community (his and his wife's graves may still be found in the Jewish cemetery in Happy Valley). Prior to the Raymonds, from about 1932, three brothers from Bahrain, surnamed Edgar and also Jewish, lived there. During that time, 39 Stubbs Road was sometimes referred to as “Flowerburn”, suggesting an even earlier Scottish owner or builder.

With six young children all at home, despite or because of their ample staff, Zing Wei had a complex household to oversee. Han Liang was presumably continuing to make his regular, lengthy business trips to the Philippines. Amid the relative comfort, they must also have had constant worries about the chaotic situation "back home"; the Yuyuen Road house which at some point was commandeered by the Japanese; the children's eventual schooling... in sum, their and their country's future.

Over the border "back home", Chiang Kai-shek was waging a full-scale war against Japan with scant resources. In the aftermath of the 1937 invasion, Chiang had retreated from Nanking, and in 1938 moved his government first to Wuhan (武漢) and then to Chungking in Szechuan Province (四川省重慶市 Sichuan Sheng Chongqing Shi). Thousands of ordinary citizens followed the KMT to the interior and, as best they could, re-set up entire universities, factories and social service programs – trying to sustain not only a war machine, but also some semblance of the modern society they had only recently created. Chiang was managing an adversarial united front with the Communist Party, continuing to receive some Russian support, and even paying for German military advice. But as Europe inched to its own war, no Western power had been willing to come to China's rescue.

Then, in late 1941, from their terrace on Stubbs Road, the Huangs saw a new phase of war arrive.

On the morning of December 8, so the story goes, Han Liang and Zing Wei returned from an all-night party. At 8:00 am Japanese bombers streaked across the sky, pelting Kai Tak airport in Kowloon on the other side of the harbor. Like many witnesses of the time, Peter describes the falling bombs as looking remarkably like thermos bottles.

They would quickly learn that this attack was part of a coordinated effort by the Japanese to expand beyond China and take on the Americans and British to launch a "Greater East Asia War." Eight hours earlier, the Japanese had launched a direct assault on the US at Pearl Harbor (on the morning of December 7 by Hawaii time). Simultaneous to Hong Kong, they attacked British and US bases in Singapore, Malaya, Manila, Guam and Wake Island. French and Dutch territories and other nations were also affected. Amid these larger assaults, the Japanese also made a symbolic attack on the American and British in Shanghai by capturing and sinking two non-essential gunboats.

That same day, Hong Kong's northern border was overrun when some 60,000 Japanese troops poured over the Sham Chun River (深圳河 Shenzhen He) into the New Territories. A small defense force of British, Indian and Canadian troops, supplemented by a volunteer corps, was outnumbered by more than three to one. On December 11, the defending troops retreated south to Hong Kong island. On December 15, the Japanese began to bomb the island’s northern harbor-side shore. On December 18, after the British refused two offers to surrender, the Japanese landed at Taikoo close to the eastern mouth of the harbor. One week later, British Governor Mark Young surrendered. The Christmas Day surrender was signed at the Peninsula Hotel, soon to be renamed the Matsumoto Hotel. There had been 2,000 casualties on each side, plus about 4,000 civilian deaths and a similar number of wounded.

The Huangs remained in their house for only a couple days. Because their end of Stubbs Road near Wong Nai Chung Gap was a major north-south thoroughfare across the island, once it was known the Japanese were going to overrun Hong Kong island from Repulse Bay on its southern shore, the family moved to an apartment near the Lee Gardens in Causeway Bay. The children now slept six to a cot. They remember a shell coming through a bedroom wall one night. They also recall living in mountain-side dugouts for a time.

Over the border "back home", Chiang Kai-shek was waging a full-scale war against Japan with scant resources. In the aftermath of the 1937 invasion, Chiang had retreated from Nanking, and in 1938 moved his government first to Wuhan (武漢) and then to Chungking in Szechuan Province (四川省重慶市 Sichuan Sheng Chongqing Shi). Thousands of ordinary citizens followed the KMT to the interior and, as best they could, re-set up entire universities, factories and social service programs – trying to sustain not only a war machine, but also some semblance of the modern society they had only recently created. Chiang was managing an adversarial united front with the Communist Party, continuing to receive some Russian support, and even paying for German military advice. But as Europe inched to its own war, no Western power had been willing to come to China's rescue.

Then, in late 1941, from their terrace on Stubbs Road, the Huangs saw a new phase of war arrive.

On the morning of December 8, so the story goes, Han Liang and Zing Wei returned from an all-night party. At 8:00 am Japanese bombers streaked across the sky, pelting Kai Tak airport in Kowloon on the other side of the harbor. Like many witnesses of the time, Peter describes the falling bombs as looking remarkably like thermos bottles.

They would quickly learn that this attack was part of a coordinated effort by the Japanese to expand beyond China and take on the Americans and British to launch a "Greater East Asia War." Eight hours earlier, the Japanese had launched a direct assault on the US at Pearl Harbor (on the morning of December 7 by Hawaii time). Simultaneous to Hong Kong, they attacked British and US bases in Singapore, Malaya, Manila, Guam and Wake Island. French and Dutch territories and other nations were also affected. Amid these larger assaults, the Japanese also made a symbolic attack on the American and British in Shanghai by capturing and sinking two non-essential gunboats.

That same day, Hong Kong's northern border was overrun when some 60,000 Japanese troops poured over the Sham Chun River (深圳河 Shenzhen He) into the New Territories. A small defense force of British, Indian and Canadian troops, supplemented by a volunteer corps, was outnumbered by more than three to one. On December 11, the defending troops retreated south to Hong Kong island. On December 15, the Japanese began to bomb the island’s northern harbor-side shore. On December 18, after the British refused two offers to surrender, the Japanese landed at Taikoo close to the eastern mouth of the harbor. One week later, British Governor Mark Young surrendered. The Christmas Day surrender was signed at the Peninsula Hotel, soon to be renamed the Matsumoto Hotel. There had been 2,000 casualties on each side, plus about 4,000 civilian deaths and a similar number of wounded.

The Huangs remained in their house for only a couple days. Because their end of Stubbs Road near Wong Nai Chung Gap was a major north-south thoroughfare across the island, once it was known the Japanese were going to overrun Hong Kong island from Repulse Bay on its southern shore, the family moved to an apartment near the Lee Gardens in Causeway Bay. The children now slept six to a cot. They remember a shell coming through a bedroom wall one night. They also recall living in mountain-side dugouts for a time.

This photo gives an idea of the house's commanding view of racecourse and harbor. The house would have been off the right edge of the photo. Causeway Bay was the waterfront area on the left side of the photo, with Kai Tak airport beyond it across the harbor. (https://www.hpcbristol.net, image #MF-d005, c. 1955)

Conditions in the city quickly deteriorated. In January 1942, several thousand British and other non-Chinese "enemy nationals" were interned in Stanley on the grounds of the prison and St. Stephen's College (not the same school that Mary had attended). They would remain there until the end of the war. Other schools – such as Wah Yan College and King George V School (then known as the Central British School) which the Huang children would later attend – were taken over as Japanese military hospitals. Food became so scarce that the Japanese deported the non-working Chinese population to the mainland.

Under these circumstances, the Huang family made the decision to return to Shanghai. It's not known if they had the chance to return to 39 Stubbs Road to collect their belongings or say goodbye to the household staff, who were no doubt also under pressure to return to their native places. Interestingly, what the Huang children would take back to Shanghai that would arguably become their prized possession was the Cantonese dialect. Learned on the knees of their many amahs, probably more than from their non-native parents, Cantonese had become their home language.

|

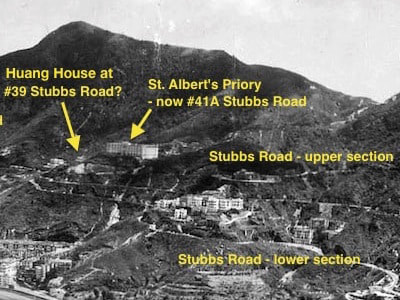

39 & 40 STUBBS ROAD & THE ADVENTISTS

39 Stubbs Road is an address that no longer exists, but present-day buildings preserve the old street numbering and offer reliable clues as to the location of the former Huang residence – as well as a future family connection to the Seventh Day Adventist Church. The annotations to the photo above take a stab at guessing which structure might be #39. Visually, the enormous St. Albert’s Priory offers a landmark. It stood from 1935 to 1962 at what has now become 41 Stubbs Road (Villa Monte Rosa). To its left were three smaller lots: one with an unknown use and a second known as “La Rue Villa” – together these two made up 40 Stubbs Road; plus a third which was the Huangs' 39 Stubbs Road, sometimes known as “Flowerburn”. The La Rue Villa site had been owned by the Seventh Day Adventist Church since 1923 and the building on it was named after an early Adventist missionary to Asia, Abram La Rue. By the 1930s, the villa housed a group of Adventist nuns. In 1939, around the time the Huangs were resident, they opened a kindergarten adjacent to an Adventist church on Ventris Road next to the Happy Valley race course, which their house overlooked.

|

Helen would later join the Adventist Church, following an introduction by her mother. Zing Wei is believed to have developed an interest in the church at some point when the family lived near an Adventist center, but it's not known if that was in Hong Kong or Shanghai. It seems plausible that the acquaintance developed during this time period when the Huangs lived immediately next door to La Rue Villa and its nuns.

In the late 1960s, the Seventh Day Adventists wanted to build a hospital in Hong Kong. They created a large parcel of land by merging their existing La Rue site with the other #40 site and the #39 site (each was about two-thirds of an acre), if not additional land as well. The address of the well known Hong Kong Adventist Hospital address remains 40 Stubbs Road – a "close enough" reference point for a present-day sleuth seeking the location of the Huangs' wartime abode. SOURCES

|