First Lessons

? to 1908

|

Most of the foreigners who resided in Amoy lived on a small outlying island, called "Kulangsu" in the local dialect (鼓浪嶼 Gulangyu). Removed but a convenient boat ride away from Amoy Island, this was the desirable enclave for the city's 500 or so foreign residents, along with seven or eight thousand Chinese.

Here were cricket fields and tennis courts, foreign consulates, and the headquarters of the Municipal Council and Customs Commission that not only allowed the foreigners to govern themselves within Chinese territory but also to run Amoy's customs service. Around this time, wealthy Chinese – generally those who had made their fortunes overseas – also began to build houses on Kulangsu. |

It is believed that Han Liang may have grown up at least partly on Kulangsu, but it is not known for sure. His brother Han Ho would definitely live there with their mother Yu Koon in the mid-1920s. By that time, it’s also known with certainty that Uncle Been-Sa's wife and children lived on Cao Pu Di (草埔地) in the heart of Amoy's old walled city center . But nothing earlier is known with precision.

In his adult life, Han Liang would say he hailed from "Siming" (思明), an evocative name that unfortunately for modern-day sleuths locates him more in time and generation than place. Siming was an old name for Amoy still current in Han Liang’s time. It meant "Remember the Ming", referring to the 17th century transition from the Ming to Qing dynasties when Amoy and Taiwan were the base of a pirate-patriot who led an anti-Qing resistance that went unquelled for forty years. His name was Koxinga (國姓爺 Guo Xing Ye).

Nowadays, pretty much the full extent of what was Amoy back in Han Liang’s time, including Kulangsu Island, is merely one district of modern-day Xiamen, and that whole district is called “Siming”. So Han Liang’s use of “Siming” appears to offer no confirmation of whether as a child he lived on Kulangsu or in the former walled city and waterfront area, as his Uncle Been-Sa's family is known to have done, or whether at some earlier point they might all have resided in the ancestral village of Wenzao, slightly east of Amoy's old city walls.

Given Kulangsu's cachet, one would think that if Han Liang and his brother had lived there as children, Han Liang might have said he came from "Amoy Kulangsu" or "Siming Kulangsu". Thus, having come of age at a time of rising anti-Qing sentiment, Han Liang's use of the name "Siming" was perhaps not a geographic reference, but rather a show of Chinese nationalism or simply a nostalgic reference to a bygone era.

In his adult life, Han Liang would say he hailed from "Siming" (思明), an evocative name that unfortunately for modern-day sleuths locates him more in time and generation than place. Siming was an old name for Amoy still current in Han Liang’s time. It meant "Remember the Ming", referring to the 17th century transition from the Ming to Qing dynasties when Amoy and Taiwan were the base of a pirate-patriot who led an anti-Qing resistance that went unquelled for forty years. His name was Koxinga (國姓爺 Guo Xing Ye).

Nowadays, pretty much the full extent of what was Amoy back in Han Liang’s time, including Kulangsu Island, is merely one district of modern-day Xiamen, and that whole district is called “Siming”. So Han Liang’s use of “Siming” appears to offer no confirmation of whether as a child he lived on Kulangsu or in the former walled city and waterfront area, as his Uncle Been-Sa's family is known to have done, or whether at some earlier point they might all have resided in the ancestral village of Wenzao, slightly east of Amoy's old city walls.

Given Kulangsu's cachet, one would think that if Han Liang and his brother had lived there as children, Han Liang might have said he came from "Amoy Kulangsu" or "Siming Kulangsu". Thus, having come of age at a time of rising anti-Qing sentiment, Han Liang's use of the name "Siming" was perhaps not a geographic reference, but rather a show of Chinese nationalism or simply a nostalgic reference to a bygone era.

Assuming the Huang brothers did live on Kulangsu as children, did they live there when their father was alive? Or only after his death and the imperial decree that abolished the exam system? Was the boys' education something that both parents had discussed? Or had Yu Koon like Mencius' mother acted on her own initiative, moving her sons to where she thought the best educational opportunities lay – in this case, Amoy's foreign enclave?

For some years, with the Japanese model of rapid reforms in mind, the Qing court tried to establish a compulsory, government-sponsored education system that would start from the age of seven. But funds were scarce and implementation sporadic. In the breach, apart from the schools run by missionaries, local elites also strived to start more modern schools. Even if there were different opportunities on Kulangsu, Han Liang's early education by his own account remained a traditional one. One story goes that Han Liang and Han Ho carried their own desks and chairs to the local schoolmaster's, a vignette that conjures up the kind of local school that prosperous families throughout China and throughout the ages had subsidized to provide basic literacy to neighborhood children, who were usually extended clan members.

As a student of the old system, a boy's task would have been to memorize reams of set texts in order to master the highly formulaic essay style required for the centrally administered exams held at the county, provincial, and finally, capital levels. The goal would have been to secure a position in the imperial bureaucracy. Failed exam-takers often became schoolmasters. The system was so codified that we can safely assume that Han Liang and Han Ho learned to read and write from the "Three Character Classic" (三字經 San Zi Jing), which dates from the Sung Dynasty and mentions Mencius and his mother, and the even older "Thousand Character Essay" (千字文 Qian Zi Wen). The Chinese heading at the top of this page is a line from the Three Character Classic that says, "If the child does not learn, all is not right" (子不學 非所宜 zi bu xue, fei suo yi).

For some years, with the Japanese model of rapid reforms in mind, the Qing court tried to establish a compulsory, government-sponsored education system that would start from the age of seven. But funds were scarce and implementation sporadic. In the breach, apart from the schools run by missionaries, local elites also strived to start more modern schools. Even if there were different opportunities on Kulangsu, Han Liang's early education by his own account remained a traditional one. One story goes that Han Liang and Han Ho carried their own desks and chairs to the local schoolmaster's, a vignette that conjures up the kind of local school that prosperous families throughout China and throughout the ages had subsidized to provide basic literacy to neighborhood children, who were usually extended clan members.

As a student of the old system, a boy's task would have been to memorize reams of set texts in order to master the highly formulaic essay style required for the centrally administered exams held at the county, provincial, and finally, capital levels. The goal would have been to secure a position in the imperial bureaucracy. Failed exam-takers often became schoolmasters. The system was so codified that we can safely assume that Han Liang and Han Ho learned to read and write from the "Three Character Classic" (三字經 San Zi Jing), which dates from the Sung Dynasty and mentions Mencius and his mother, and the even older "Thousand Character Essay" (千字文 Qian Zi Wen). The Chinese heading at the top of this page is a line from the Three Character Classic that says, "If the child does not learn, all is not right" (子不學 非所宜 zi bu xue, fei suo yi).

That Han Liang and Han Ho could pursue their education into their teens, rather than be pressed to work or emigrate overseas as laborers, demonstrates that they were already well above the common fray in Amoy. In the late 19th century, something like 100,000 Fukienese were shipped to Peru to mine guano for fertilizer – an almost inevitable death sentence. In 1902, from Amoy alone, another 100,000 men left to work on plantations in Malaya.

|

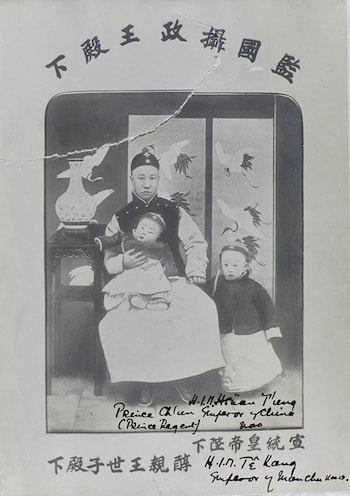

In this patchy landscape, the greatest educational edge available to Han Liang and Han Ho might simply have been the ability to stay alert to the novelties that a port city laid before them. On October 30, 1908, for example, four American battleships sailed into Amoy harbor after a half year voyage through the Straits of Magellan and across the Pacific. They formed a satellite to a larger fleet headed to the Philippines, a US territory for the past decade. In Amoy, there were months of preparations, and a Manchu prince was even sent from Peking (北京 Beijing) to host the thousands of American servicemen who would disembark from these giant war ships.

Presuming this prince hastened back to Peking after extending imperial hospitality, he would have arrived just in time to learn of the emperor's death on November 14, followed the next day by the death of the emperor's aunt, Empress Dowager Cixi (慈禧太后 Cixi Tai Hou). It was she who had really held power over the past decades while first her young son and later her nephew, Guangxu (光緒), sat on the throne. The Qing court had experimented with modernization, but weakly and insufficiently. Now with another boy prince – Puyi – tapped as imperial successor, the Qing court was no closer to helping China find its place in the 20th century world order. Was Han Liang dazzled or shocked? As the new century unfolded, such foreign displays of might and court upheavals were perhaps less and less remarkable – and in any case, by late 1908, he was no longer living in Amoy. |

SOURCES

|

The visit of the battleships and prince is related in:

|

|