PhD Years

Columbia University, 1915-1918

For further studies, Han Liang went on to Columbia. With an enrollment of over 12,500, the university was the world's largest and a magnet because of its diverse graduate programs. Han Liang earned his AM in politics in 1916 and PhD in economics in 1918. During this time, he trained his attention on the very real problem of how to keep China’s nascent republic afloat financially – a concern that would be highly relevant throughout his entire working life and that he would directly confront in fourteen years’ time.

Like many of his classmates, Han Liang was also drawn to the ideas of the then-current Progressive Movement.

Like many of his classmates, Han Liang was also drawn to the ideas of the then-current Progressive Movement.

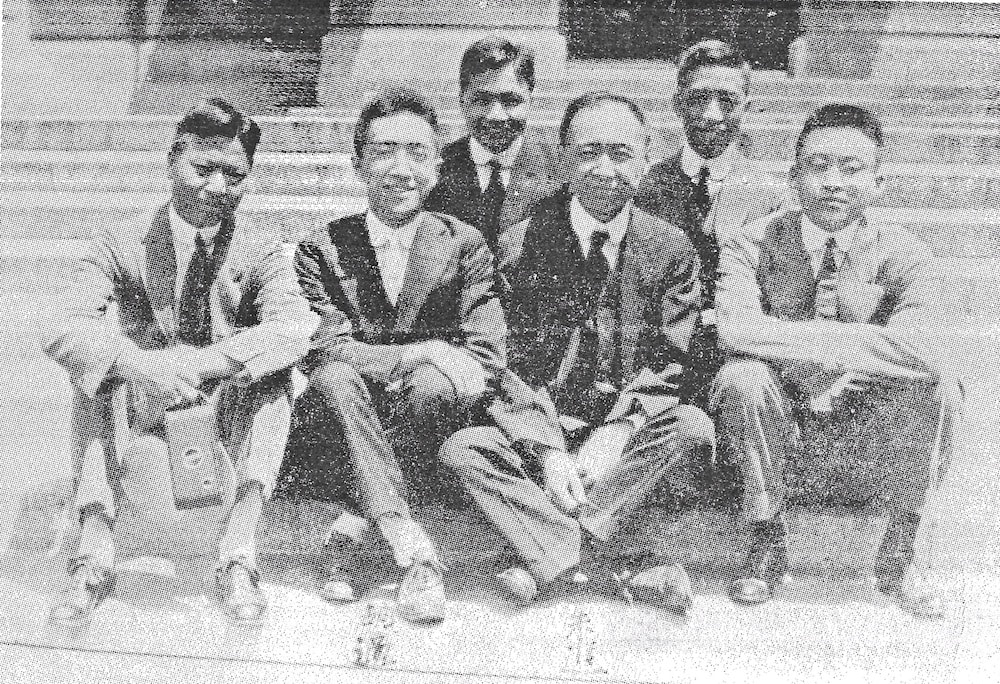

Han Liang (back row center) pictured soon after he entered Columbia and looking very happy. He is with Hu Shih (胡適 Hu Shi, front 2nd from left), who would already have had a reputation as someone with literary polish, and who would very soon become an eminent philosopher and writer; and Tao Hsing Chih (陶行知 Tao Xingzhi, front right), a future proponent of mass education. Both Hu and Tao were extremely influenced by social reformer John Dewey, then teaching philosophy at Columbia. Seated between them is believed to be Chu Chin (朱進), an economics and sociology student writing his dissertation on “The Tariff Problem in China”, a topic similar to Han Liang's. The others are not identified.

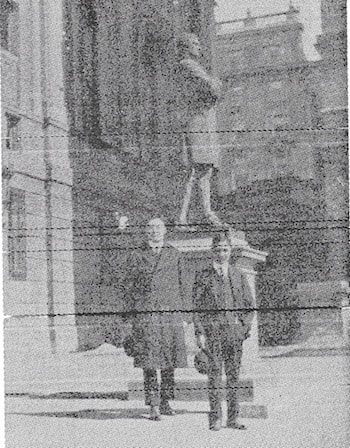

Han Liang pictured again with Tao Hsing Chih, who sent this photo home with the message: “Presented to my loving and beloved Mother, Wife and Sister. Accept this small token. Respectfully. (Standing on the right is Huang Han Liang Esquire.)” They stand in front of Alexander Hamilton's statue, outside Hamilton Hall.

|

If at Princeton he had been known as an orator, at Columbia Han Liang's record was more that of a writer. His major oeuvre was his doctoral dissertation on The Land Tax in China. Tracing his subject from 2,697 BCE to the current day, Han Liang synthesized centuries of Chinese writings about land holding and taxation with contemporary proposals for tax reform coming mainly from the West. It remains available today and as such may be considered his most tangible legacy (apart from his children).

Han Liang’s stated aim was “to contribute something toward the solution...of the present financial embarrassments”. These were great indeed. Just paying off the partially-forgiven Boxer Indemnities would require all of China’s customs duties for the next twenty-plus years. The salt “gabelle” had potential to generate additional revenue, but was earmarked to service the country’s debts. Only in land taxation did Han Liang see a chance for the government to find the kind of income it would need to run a modern nation. In his final chapter, Han Liang reviewed in some detail the ideas of his Princeton professor, William Willoughby, who had been named Constitutional Advisor to Yuan Shikai in 1915 and who himself had published a “Memorandum on the Reform of the Land Tax System in China” in 1916 and 1917. |

Sadly, neither Willoughby's nor Han Liang’s advice would be of any of use to China for some time. Yuan died in mid-1916 after a hugely unpopular effort to revive the monarchy with himself installed as emperor. In the worrisome void left after his inadequate and self-aggrandizing leadership, regional warlords (軍閥 jun fa) began to vie for power with their private armies. Now was beginning the kind of chaos that had not happened in 1911 or 1912 when the Qing court crumbled, but which Chinese know to fear when there is dynastic change.

In sharp contrast, Han Liang continued to learn what he could from the reform movements taking place in the US. Like Hu Shih and Tao Hsing Chih (pictured above), who fell under John Dewey's spell, Han Liang learned from professors who were at the heart of a lively circle of New York progressives and who had utter faith in the ability of the social sciences to solve society’s ills. As he relates, most memorable among them was Edwin Seligman, who gave “inspiring encouragement and guidance” as Han Liang’s thesis advisor. Son of a prominent banking family, ardent advocate of the progressive tax, co-founder of the New School for Social Research, and first president of the Urban League, Seligman taught Han Liang for three years.

In sharp contrast, Han Liang continued to learn what he could from the reform movements taking place in the US. Like Hu Shih and Tao Hsing Chih (pictured above), who fell under John Dewey's spell, Han Liang learned from professors who were at the heart of a lively circle of New York progressives and who had utter faith in the ability of the social sciences to solve society’s ills. As he relates, most memorable among them was Edwin Seligman, who gave “inspiring encouragement and guidance” as Han Liang’s thesis advisor. Son of a prominent banking family, ardent advocate of the progressive tax, co-founder of the New School for Social Research, and first president of the Urban League, Seligman taught Han Liang for three years.

Sociology and politics were Han Liang's minors. His professors included Franklin Giddings, the first person to hold a professorship of sociology in the US, as well as groundbreaking historian Charles Beard, who posited that America's founding fathers were more motivated by economics than philosophical principles. Robert Haig, a noted tax theoretician, made comments on his manuscript.

Han Liang credited Jeremiah Whipple Jenks with having suggested his dissertation topic. Jenks was director of New York University's "Far Eastern Bureau", which "prompt[ed] a better understanding by the spreading of accurate information about China." Han Liang worked at the Bureau for over a year.

Han Liang credited Jeremiah Whipple Jenks with having suggested his dissertation topic. Jenks was director of New York University's "Far Eastern Bureau", which "prompt[ed] a better understanding by the spreading of accurate information about China." Han Liang worked at the Bureau for over a year.

A long-time China-watcher, Jeremiah Jenks had tried to put China on the gold standard earlier in the century while serving as an International Exchange Commissioner. Ironically, he also tried to persuade Roosevelt to use the Boxer Indemnity overpayment to help China’s currency reform, rather than to support the scholarships that ultimately made it possible for Han Liang to go to the US.

As we will learn, it appears that Han Liang was also making another intriguing contact beyond the confines of the Columbia campus.