Cream of the Crop

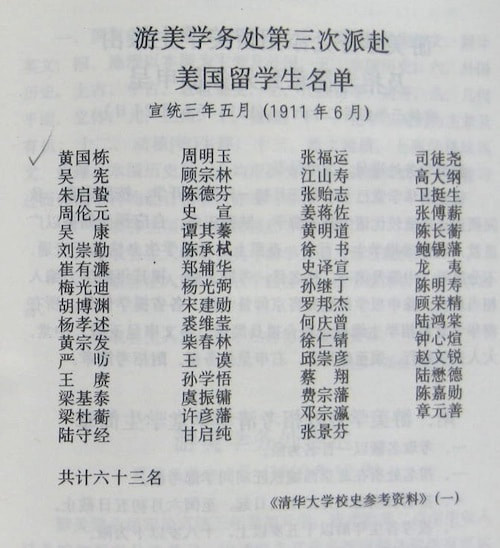

Tsinghua Pioneer & Indemnity Scholar, 1911

Amid all the registrations and rounds of testing, another important cohort of people arrived in Peking: Tsinghua's first teachers.

The inaugural faculty for this landmark mission were seventeen Americans handpicked by John Mott, the head of the YMCA and a Methodist. Considering that their students would be all-male, it comes as something of a surprise to learn that they were nine female and eight male teachers. Not all their names come down to us, but they included Julia and Beatrice Pickett, presumably related, who would teach History and German, and another pair, Emma and Isabel Liggett, who would do double-duty teaching English, plus Math and Geography, respectively, as well as Thomas Breece (English and Latin), Peter Wold (Physics), Florence Starr (Painting), a Mr. Sharpe (Music), Arthur Shoemaker (Athletic Director) and Richard Bolt (School Physician).

The inaugural faculty for this landmark mission were seventeen Americans handpicked by John Mott, the head of the YMCA and a Methodist. Considering that their students would be all-male, it comes as something of a surprise to learn that they were nine female and eight male teachers. Not all their names come down to us, but they included Julia and Beatrice Pickett, presumably related, who would teach History and German, and another pair, Emma and Isabel Liggett, who would do double-duty teaching English, plus Math and Geography, respectively, as well as Thomas Breece (English and Latin), Peter Wold (Physics), Florence Starr (Painting), a Mr. Sharpe (Music), Arthur Shoemaker (Athletic Director) and Richard Bolt (School Physician).

|

The students officially enrolled in batches: the provincial group on March 19, the open exam group on March 21, and the 1910 group on March 23. On March 30 there was an opening ceremony for the 310 students who would make up the high school section and on April 1 for the 150 of the higher education section, who included Han Liang. Perhaps bizarrely given the school's westernizing mission, the students lined up by rank order according to their exam results and kneeled and kowtowed before their elders – nine times, as though presenting themselves to the emperor. Speeches were made exhorting them to study hard, and they also made offerings to Confucius. On April 29, there would be further festivities to mark the the formal opening of the “Tsing Hua Imperial College” (帝國清華學堂 Diguo Qinghua Xuetang). The more urgent milestone was that of Monday, April 3, when classes began. If it had ever lifted, the pressure was now back on. Han Liang and his 150 or so higher-ed schoolmates had barely twelve weeks till the final exams which would determine which of them would go to the US. |

We must guess what they went through based on what's known about the prior two years. In 1909, the candidates sat for two rounds of exams held over five days in August. In the first round, they were tested in Chinese, English, Chinese history and geography, and 640 students were knocked down to about 100. In the second round, they were tested in math, sciences, world history and geography, and the 100 was winnowed to a final forty-seven. The exams held in July 1910 were said to be more difficult, requiring greater English proficiency, as well as translation from German, French or Latin. Out of the second year’s candidates, seventy students were selected.

In 1911, for Han Liang's cohort, the large cull had already happened earlier in the process, so perhaps fifty-fifty odds didn't seem that bad. We are told that 134 students sat for the five days of exams that began on June 23, suggesting further attrition since March. After three months in the classroom, Han Liang would certainly have known his competition, making one wonder whether these new Tsinghua classmates were collegial or cutthroat, and whether Han Liang was confident or on edge. If one shivers to think of his arrival in Peking in February, one sweats in sympathy imagining how hot and slow those summer days must have been while their papers were marked.

In the end, Han Liang's years of intense study paid off. When the "Golden Roster" (金榜 Jin Bang) was published – to use the term for the old exam honor roll, his name was one of sixty-three listed. Not only was he on the list, which was presented in rank order, he was also the top-scorer. As he explained it a few years later, he had achieved “the highest average among all competitors”. Apparently, the final marks were based 50% on exam results and 50% on course grades.

In the end, Han Liang's years of intense study paid off. When the "Golden Roster" (金榜 Jin Bang) was published – to use the term for the old exam honor roll, his name was one of sixty-three listed. Not only was he on the list, which was presented in rank order, he was also the top-scorer. As he explained it a few years later, he had achieved “the highest average among all competitors”. Apparently, the final marks were based 50% on exam results and 50% on course grades.

|

|

It bears explaining that in a further twist, the name heading the list of sixty-three successful exam-takers was not "Han Liang" but rather an alias that we are told Han Liang adopted to avoid offending Qing sensibilities – a further sign of the unsettled times and burgeoning anti-Manchu nationalism. His name appeared not as “Huang Han Liang” (黃漢樑) – “Pillar of the Han", but as “Huang Kuo Tong” (黃國棟 / 黄国栋 Guo Dong) – “Pillar of the Nation” (see note below). We do not know if he took on this name while at the Anglo-Chinese College or only in anticipation of the Peking exams. At first glance, a name change seems overly cautious. There must have been plenty of Chinese names with the Han character. But it is possible that his name took on an extra tinge when coupled with the fact that he hailed from Amoy, which had been the home base of pirate-patriot Koxinga (國姓爺 Guo Xing Ye), who led a long-standing anti-Qing resistance. Now two centuries later, did Han Liang have a view of himself as a patriot or potential patriot? Did he see his efforts as a means to help strengthen China? Or was he only thinking about fulfilling personal ambitions, or maybe simply seeking to do his mother proud? |

One wonders how Han Liang even conveyed the good news to his mother. Would his school in Foochow have been telegraphed? Would Han Ho have shared the news on his next trip home – their mother chiding him to do as well when his turn came? Or might a letter have been read aloud to Yu Koon, making her the talk of their neighborhood?

It’s tempting to imagine the pause of elation that Han Liang must have enjoyed, if only for the briefest of moments, before the next stage of unknowns. For a week or month or year, he was the best in the nation, and his future was limitless.

It’s tempting to imagine the pause of elation that Han Liang must have enjoyed, if only for the briefest of moments, before the next stage of unknowns. For a week or month or year, he was the best in the nation, and his future was limitless.

|

*PILLARS, COLUMNS & BEAMS

There is no good English equivalent for the character “liang” (樑) in Han Liang's name. Like the English “pillar”, it implies a critical element without which a structure collapses. But unlike “pillar”, it may refer to either a vertical or horizontal element – i.e., a column OR a beam, with its default meaning being a beam or horizontal element. Interestingly, in western architecture, it is pillars and columns that are carefully articulated with capitals, entasis, fluting, etc. and beams that are undifferentiated. |

By contrast, in Chinese tradition, beams are the architectural elements that are purposefully fashioned and often intricately carved, while pillars tend to be undifferentiated posts.

SOURCES

|